The Virgin Mary: Art, Materiality, and Piety

Curated by Daniel Ymbong

The establishment of the Spanish viceroyalties ushered in the creation of new popular devotions and art production depicting the Virgin Mary in the Americas in the Early Modern period. The great demand for Marian images beginning in the sixteenth century led to the establishment of artists' guilds, workshops, and schools, which produced artworks to adorn public and private spaces. Marian images and devotions became part of the diverse visual cultures in Latin America, informing the daily lives of populations in colonial Mexico and Peru, so much so that the devotion to Mary would inspire revolution and continue to permeate present-day spirituality and identity in Latin America. This miniature exhibition explores the origins, diaspora, and transformations of Marian iconography from the IMAS Permanent Collection that are available to be experienced here in the Rio Grande Valley.

European images including included sculptures, paintings, prints, and jewelry incorporated pendants, rosaries, and scapulars from the Early Modern and Baroque periods. Marian devotions included these references in images with universal titles such as: the Virgin and Child with St. John the Baptist, the Virgin of Sorrows, the Virgin of the Rosary, the Virgin of Mount Carmel, the Immaculate Conception, the Assumption, the Coronation, the Virgin of the Candlemas, the Pietà, the Virgin of Light, the Virgin of Mercy, and the Virgin of Loreto.

Unique Iberian devotions included: the Virgin of Solitude, the Virgin of Guadalupe Extremadura, the Virgin of the Rule, the Virgin of the Pillar, the Virgin of Remedies, the Virgin of Montserrat, the Divine Shepherdess, Our Lady of Arantzau and the child Mary depicted in her life and death. Religious orders commissioned specific Marian works, naming their organizations as tribute. These included the Carmelites’ Virgin of Mount Carmel, the Conceptionists’ Virgin of the Immaculate Conception, and the Mercedarians’ Virgin of Mercy.

Both artists and artisans creatively reproduced and reinterpreted the large corpus of European Marian devotions. Their interpretations of the Virgin created new and localized hybrid forms, which were unique to the Spanish viceroyalties. Cultural norms such as race, hair, garment, accessories, medium, artistic genre, and inclusion of local flora, fauna, and animals are depicted in the images of Mary. Prominent examples of localized Marian devotions include the Virgin of Guadalupe in Mexico, the Virgin of Pomata in Peru, whose crown of multi-colored plumes are of Inca origin, and the winged Virgin of the Apocalypse throughout the Spanish colonial milieu. These Marian devotions display overt examples of both indigenous and European mestizaje (mixing), which contributed to local cultural expressions, negotiations, and inventions.

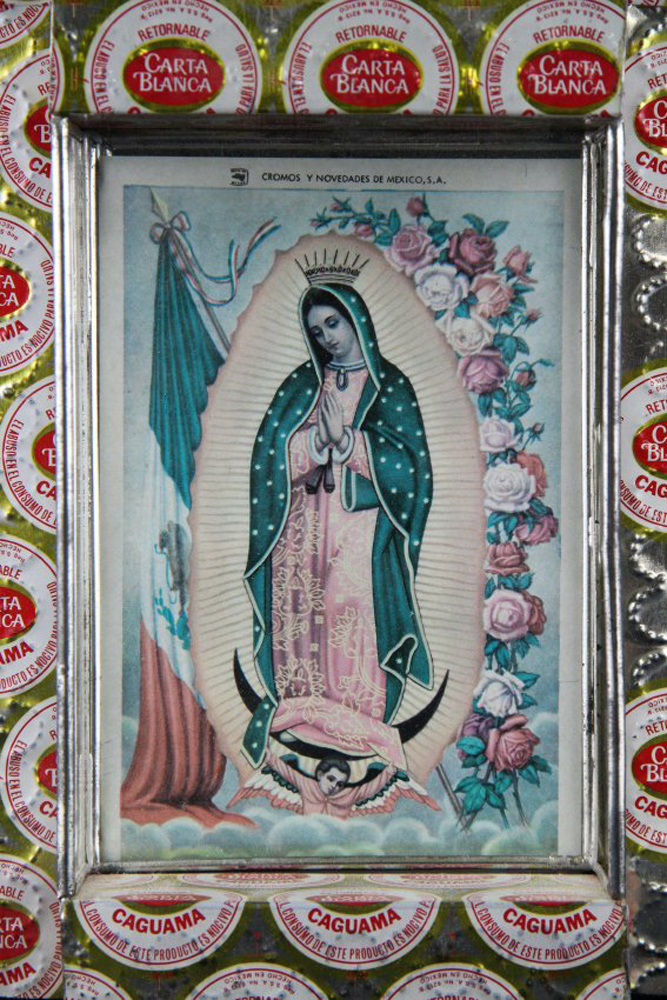

Of all the Marian devotions in the Spanish viceroyalties, the Virgin of Guadalupe established a cult presence. The Guadalupe appears of mix race with dark skin tonalities. She embodies Aztec iconography, evident in her vestment’s inclusion of quincunx flowers. Her center-split hair and cinched sash are Aztec styles, referencing her place of appearance in Tepeyac that was once the temple of the mother goddess Tonatzin.

Her supernatural apparition coupled with miraculous wonders, led to the production of endless images for churches, convents, schools, government palaces, and homes. Colonial artworks of Guadalupe in Bourbon Mexico were sent to Spain and signed Pinxit Mexico (Painted in Mexico). Strict guidelines for reproduction was mandated by art guilds, workshops and schools. Entrepreneurial artists and artisans in Peru like the Cuzco School fashioned their own versions of the Guadalupe, incorporating gold-leaf rendering to emulate brocade. The Cuzco School created artworks for export to Italy, and within the viceroyalty, to present-day Colombia, Buenos Aires, and Bolivia. Spanish colonial artworks also merged various mediums such as: feathers, silk, brocade, ivory, mother of pearl, Columbian emeralds, and Asian lacquer via the Manila Gaellons.

Colonists used these devotional images as visual displays of spiritual piety and storytelling. These images dictated said virtues of motherhood, domesticity, and purity for cloistered and secular women to emulate. Religious orders, churches, places, and people were named after the Virgen of Guadalupe. Originally, the Virgin of Guadalupe was venerated amongst creoles (Europeans born in the colonies) and later became the patroness of Mexico, the Americas, and the Philippines. Her veneration inspired a national resistance and independence from colonial rule in Mexico, which has profoundly impacted contemporary Latinx identity in the borderlands and in Mexico and America as well.

From Renaissance oil paintings, Baroque pyramidal cloaked sculptures, to stylized brightly colored ofrendas (altars) of Arte Popular (Popular Art) to the Rasquache kitsch reclamation of the Latinx vernacular, the Virgin Mary has and still is a complex visual symbol of mestizaje, faith, unity, resistance, artifice, culture, gender, and identity.

Madonna and Child with St. John

Spanish colonial artworks referenced Spanish, Flemish, and Italian images, such as Mannerist paintings depicting the Virgin and Child swathed in pastel drapery with a crisp, paper-like rendering and elongated features. European artists also traveled to the viceroyalties. For example, the Italian Jesuit artist Bernardo Bitti (1548-1610) was sent to Peru and lived as a missionary, producing a substantial body of Mannerist paintings on his travels throughout Peru. The painting in the IMAS presents a pastel color palette and a complex composition reminiscent of the Mannerist period.

Retablo of the Sorrowful Mother

Artists and artisans reproduced popular Marian devotions such as the Virgin of Sorrows, which followed European Baroque theatricality, naturalism, and a penchant for idealized faces.

Our Lady of Solitude

Devotion to the Virgin of Solitude continued to manifest in the Spanish colonial Baroque period in Mexico and Peru, showcasing shifts in style depicting the Virgin in triangular vestments with lavish ornamentation and arched diadems in sculptures.

Virgin and Child

Painted depictions of the triangular Virgin and Child in viceregal Peru during the Baroque period featured a preference for bright color pallets in primary colors, such as red indicating the Sacred Mountain and the Ancient Peruvian devotion to Pachamama. Kneeling nude figures pray and seek help from the Virgin in this depiction.

Virgin of the Apocalypse

Spanish colonial devotions such as the winged Virgin of the Apocalypse, which originated in the Baroque period, informed the work of contemporary Mexican folk artists, such as Josefina Aguilar.

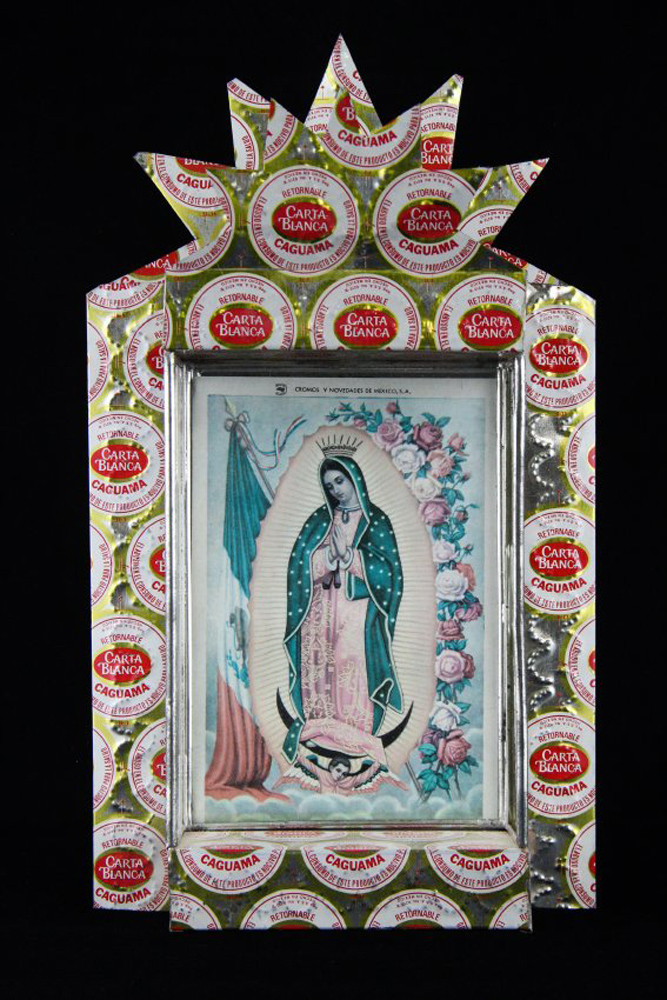

Carta Blanca Virgin of Guadalupe

The Guadalupe’s influence continued to be instrumental in the Chicano (Mexican American) Movement which began in the 1960’s, as artists juxtaposed Baroque iconography with commercial ready-made objects such as the Carta Blanca bottle caps as a commentary on cultural consumption and identity.