Border Business Briefs

Border Business Briefs are a series of publications produced by the Center for Border Economic Studies (CBEST) at The University of Texas Rio Grande Valley (UTRGV). These briefs serve as newsletters that provide insights into economic indicators and forecasts specifically focused on the Rio Grande Valley, South Texas, and North Tamaulipas regions.

Key Features of Border Business Briefs:

- Published by CBEST, a public policy research unit in the Robert C. Vackar College of Business and Entrepreneurship at UTRGV.

- Content includes:

- Economic trends and forecasts

- Trade and industry analysis

- Employment and labor market data

- Regional development insights

- Special issues may focus on long-term trends or specific topics like the impact of NAFTA.

- Recent topics include trade wars and tariff impacts in North America, with analysis from UTRGV faculty.

These briefs are designed to inform policymakers, business leaders, academics, and the broader community about the economic dynamics of the border region, supporting informed decision-making and regional development.

Current Issue

Vol 21, No.2 - Fall 2025

Private School Vouchers in Texas: Past experience and future consequences

By Maroula Khraiche, Elisa Taveras Pena, and Jean-Baptiste Tondji

On 3 May 2025, Governor Greg Abbott signed Senate Bill 2 into law, authorizing the establishment of an education savings account program (or a private school voucher program) that will allow Texan families to use at least $1 billion in public taxpayer dollars to fund their children’s private and home-school education (Edison, 2025a). Implementation of the law is expected to start in 2026. In the tug of war between parental choice in education and public education funding, parental choice prevailed. School vouchers are widely studied in economics, and the outcomes of such programs have been documented in several natural experiments. In this brief review, we examine the literature on school vouchers, including the arguments for and against them, as well as the empirical studies that have documented their impact on student outcomes.

View PDFPast Issues

Spring 2025 v20, n1

The use (and misuse) of tariffs in North America: A new trade war?

By Maroula Khraiche, Armando Lopez-Velasco, and Jean-Baptiste Tondji

Trade wars may have started. At the time this report was published, the Trump administration had threatened, then paused, a 25 percent tariff on Canadian and Mexican goods. Before the pause, Mexico and Canada were preparing retaliatory tariffs. After the pause, Trump ordered a 25 percent import tax on all steel and aluminum entering the United States to start in March 2025 and announced a plan for tariffs on US trading partners.

In this brief, we document the different perspectives and economic consequences of North American trade wars and beyond.

A Brief History of Trade Deals in North America

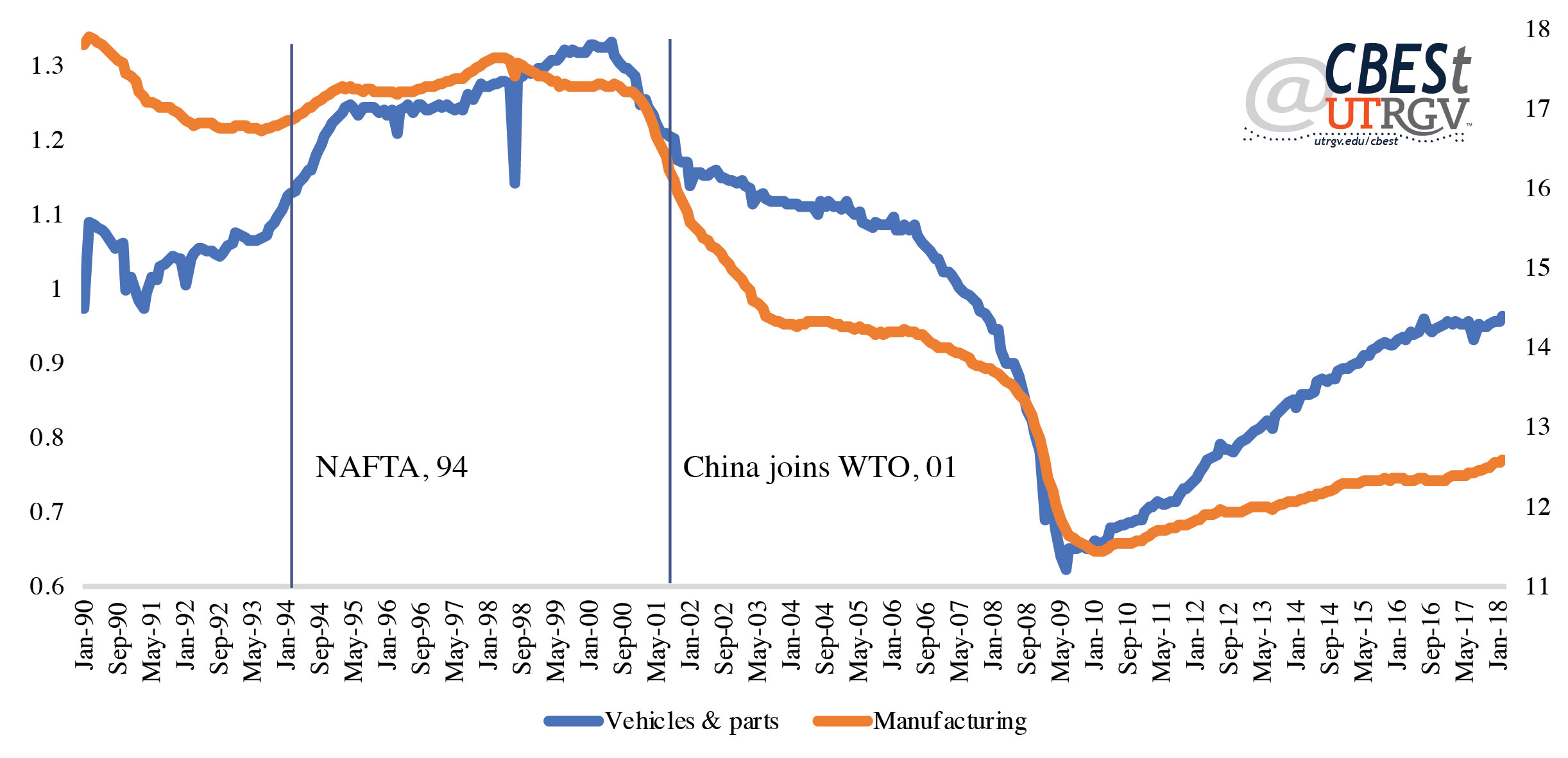

In 1964, the US and Canada signed the North American Auto Pact. Subsequently, trade in North America grew rapidly. Much of this growth was in intra-industry trade. Previously, tariff protections set by Canada and the US limited imports and exports, and in large, parallel operations were set up in each country to avoid paying tariffs, one in Canada and another in the US. American firms with Canadian subsidiaries were smaller in scale than their US counterparts and, therefore, were at a disadvantage.

The car industry is characterized by what economists call internal economies of scale. In such industries, as production rises, average costs decrease. This implies that a larger production (which can be realized when firms can sell final goods in both countries) is more cost-effective and, therefore, increases the profits of firms while reducing prices for consumers. Another benefit of allowing firms to increase production levels by accessing more markets is that more firms can participate, increasing the varieties offered to consumers. In this case, countries would both import and export cars (i.e., Intra-Industry Trade), and consumers would gain from more choices and lower prices. This is a textbook example of important gains from trade, e.g., see Krugman and Melitz (2023). The Pact confirmed this result: the number of varieties produced in Canada declined while the level of certain model cars increased. In essence, production was concentrated in fewer plants that produced higher levels. Therefore, American firms imported some models from Canada and increased their exports of others. Another benefit from rising trade was that firm-level productivity was observed. Later, in 1989, the Canada–US Free Trade Agreement expanded to include other manufacturing sectors.

Over time, the North American Free Trade Agreement between the US, Canada, and Mexico (NAFTA) was signed in 1994, and Mexico was included in the free trade zone. Eventually, trade in automotive parts, not just final goods, increased substantially. In 2018, during President Trump’s first term in office, NAFTA was renegotiated as the US-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA). In the new deal, provisions were added to improve labor standards and open the Canadian dairy market, among other adjustments.

During the renegotiation of NAFTA that resulted in the signing of the USMCA, economists calculated the costs of dissolving the free trade agreement in the continent. For instance, Head and Mayer (2019) found that consumers in all three countries would experience up to 1.4 million fewer cars being made in North America. The losses would fall disproportionally on Canada and Mexico. Given the new Trump

administration’s agenda on the US economy, it is likely that the US, Canada, and Mexico will revisit the USMCA trade agreement.

Trump’s Tariff Strategy 2.0

Given the net loss countries typically incur once trade barriers are implemented, it may be puzzling why such trade wars emerge. From an economic perspective, despite their negative effect, many countries use tariffs or taxes on imported goods to protect domestic industries, generate revenue, and address trade imbalances. Beyond economic purposes, political considerations and national security measures might also justify tariffs.

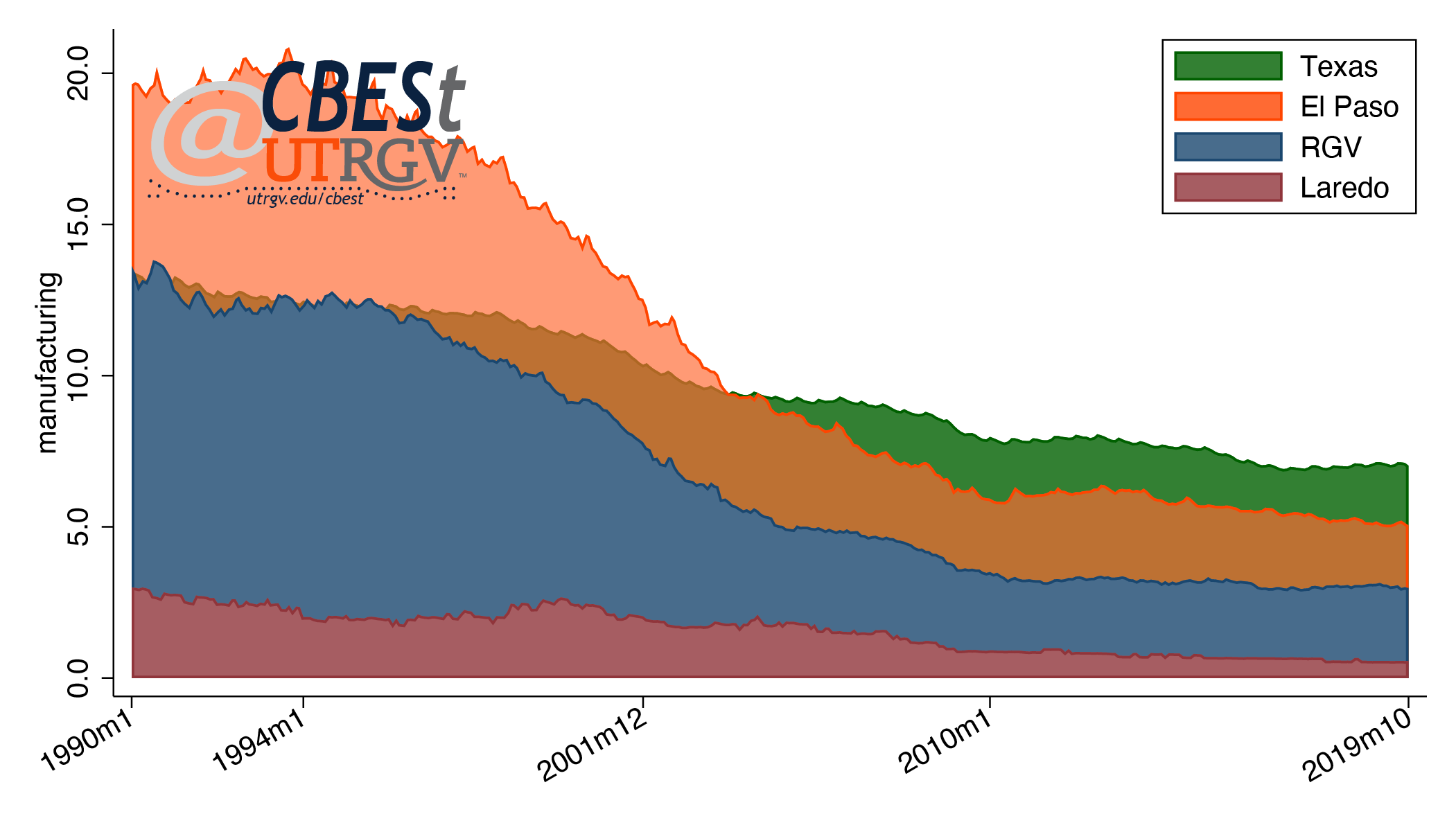

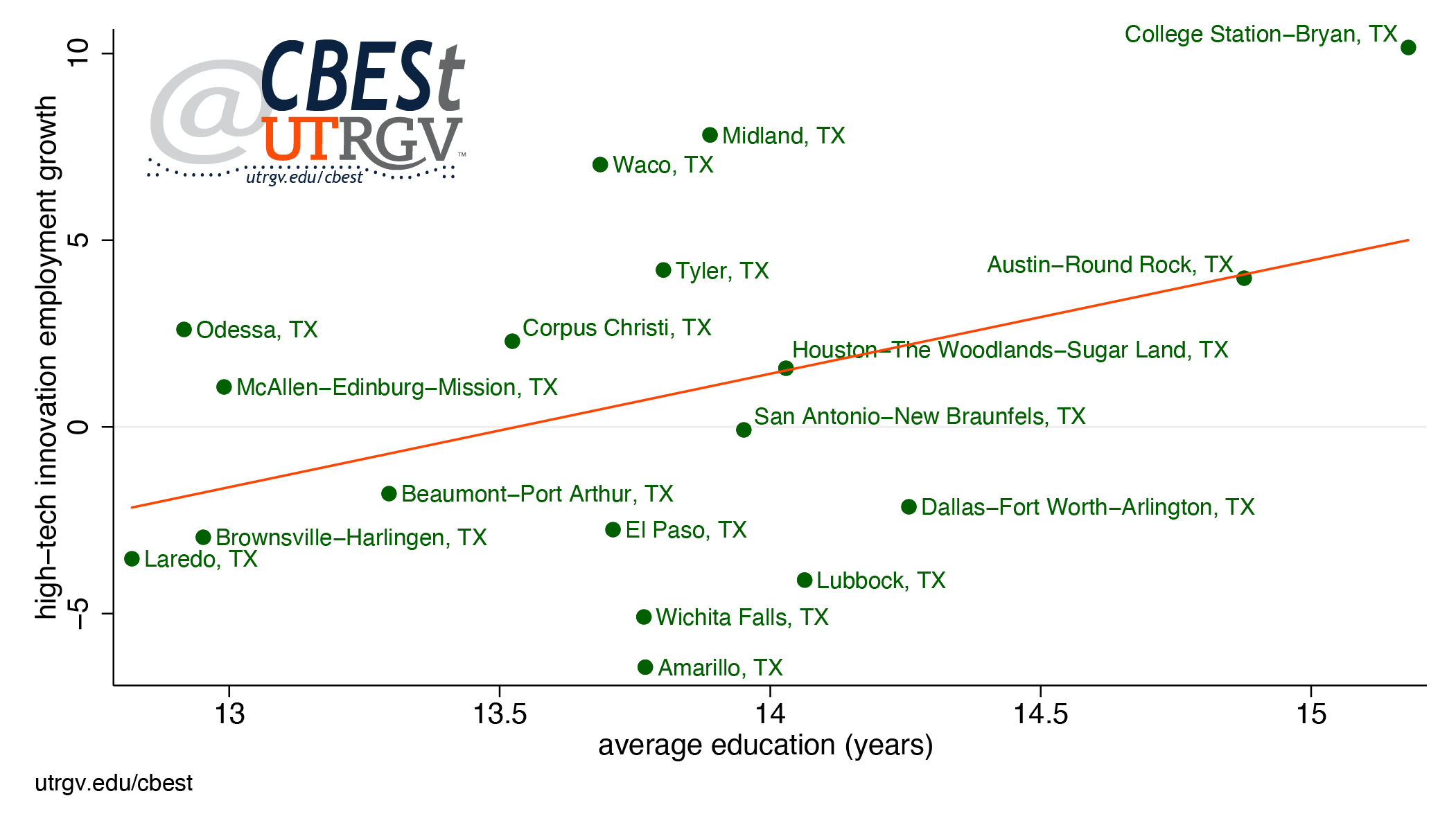

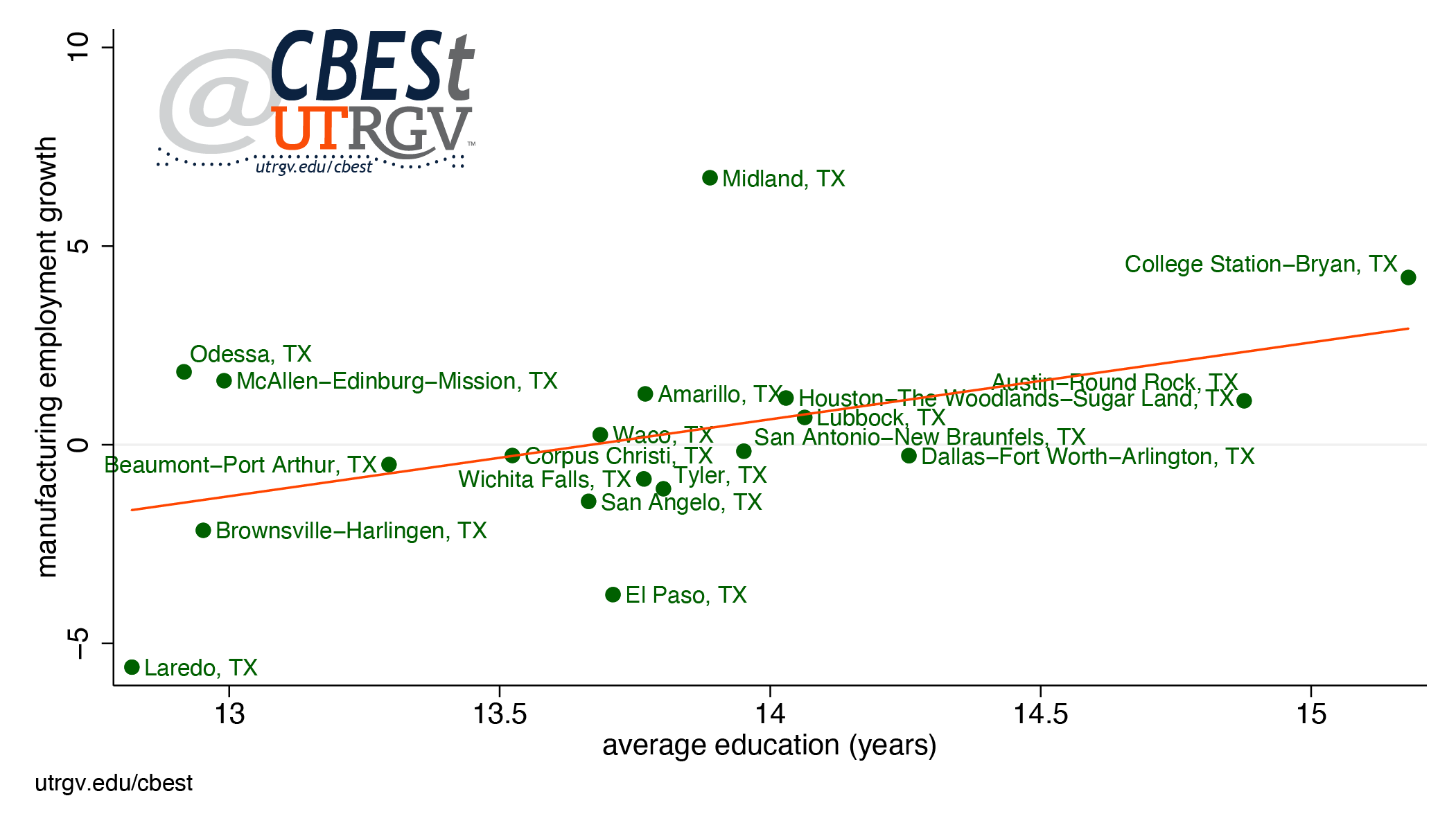

In the particular case of the recent trade wars initiated by the US, three major reasons have been used to justify Trump’s decision to levy tariffs, “the most beautiful word in the dictionary.” First, the US economy has witnessed a great decline in manufacturing jobs over the last 40 years; see, e.g., Dharshini (2025). Mr. Trump argued that jobs that used to exist in the US have migrated to other lower-wage countries like Mexico and China due to globalization and previous trade agreements. Second, Mr. Trump believes that the US is running a large trade deficit. At the same time, other countries, including its North American allies, Canada and Mexico, and those in the European Union, have had a record of significant trade surplus by selling their products to US consumers. By imposing tariffs, he expects that this would establish a level playing field. Leveraging the American economic power, he believes that these protectionist intentions would generate new trade agreements between the US and other countries that may lead to the resurrection of the manufacturing industry and boost the demand for products made in America (Reuters, 2025). The argument is that a tariff policy, mixed with an investment and growth strategy and national security policies, could boost US manufacturing.

Third, the tariffs may be seen as a negotiating tactic. After the announcement of the tariffs (later paused), Mexico and Canada have both acted to address Mr. Donald Trump’s border concerns (Boak, Verza, and Gillies (2025) and Stevis-Gridneff et al. (2025)). Mexico’s President Claudia Sheinbaum agreed to take back thousands of the first wave of migrants deported from the US and send 10,000 members of its National Guard troops to the border to focus on fentanyl smuggling, migrants, and guns. Similarly, Canada offered $1.3 billion Canadian dollars ($900 million) for border security with a package that included drones, helicopters, more border guards, and the creation of a joint task force with the US. Additionally, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau agreed to have a new “fentanyl czar” and list Mexican drug cartels as terrorist organizations.1

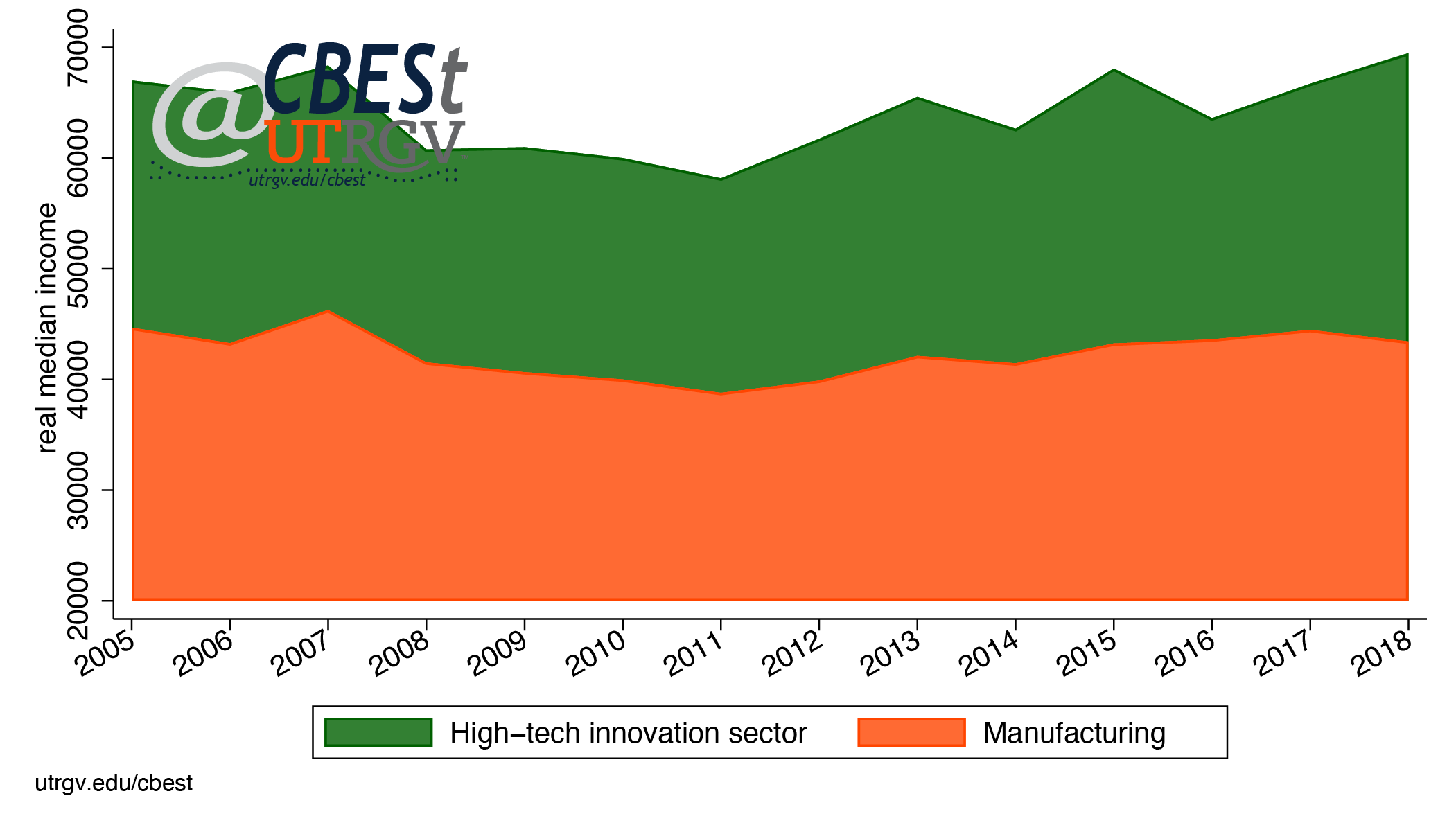

However, there are several strong counter-arguments for the motivations listed above for the trade wars. First, the US is still the “world’s largest economy of the world” (Reuters, 2025, n.d). Although the country lost manufacturing jobs that employ many working-class individuals, the American economy has also generated tremendous growth in other sectors, including technology, innovation, automation, outer space, and services, among many others. Additionally, the tariffs imposed on China during the first Trump administration failed to increase the number of jobs in manufacturing, in fact, they continued to decline. Even without a significant change in trade policy, the US is on a higher growth trajectory than other advanced economies. Secondly, economists typically doubt the importance of bilateral trade balance as a barometer of economic health. We discuss this in the following section.

The Irrelevance of Bilateral Trade Balances

As we mentioned in the previous section, the second justification President Trump has floated for using tariffs against Mexico and Canada is to “correct” the US’s bilateral trade deficit with these countries; see, e.g., Wile (2025). However, economists have long recognized that bilateral trade balances are essentially irrelevant, as the following hypothetical example illustrates.

Imagine that a school teacher buys meat from a butcher every month, while the butcher never buys anything from the school teacher. When examining the monthly trade balance between these two economic actors, it turns out that the teacher has a trade deficit every month. But is it a problem for the school teacher to have a permanent trade deficit (or for the butcher to have a permanent trade surplus with this school teacher)? The answer is no because the school teacher still produces something of value (teaching services) for people who need teaching services and who, in turn, are selling goods and services to the butcher. In that sense, having a bilateral non-zero trade balance opens up different avenues for trading and specialization (e.g., the possibility that the butcher buys bread from the baker, who in turn buys teaching services from the school teacher). Similar to the transactions of the teacher with the butcher, bilateral trade balances between countries are essentially irrelevant.

A slightly more informative magnitude would be the net trade position (also known as the “trade balance”) of the school teacher, which means adding all of the bilateral trade positions of this school teacher with any other economic actor. If the school teacher ends up with an aggregate trade surplus, then the school teacher is saving some of his or her income and, as a consequence, accumulating assets that represent future consumption. The school teacher cares about current consumption and the level of saving, but whether it has a very positive trade balance with some actors or a very negative trade balance with other actors is usually irrelevant. The school teacher would not complain to the butcher about the fact that the butcher does not buy teaching services—to the contrary, the school teacher would be happy to obtain meat.

The same analogy applies to countries in that the net trade position (once all of the trade positions with all countries are aggregated) will have a mirror representation with respect to asset accumulation: an aggregate trade surplus represents an economy that is accumulating foreign assets (thus accumulating purchasing power for future consumption from output produced in other countries). In contrast, an aggregate trade deficit represents foreign economies accumulating US assets.

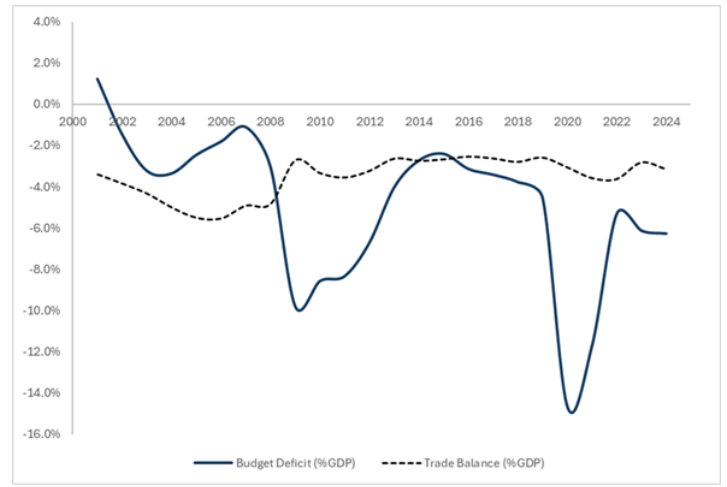

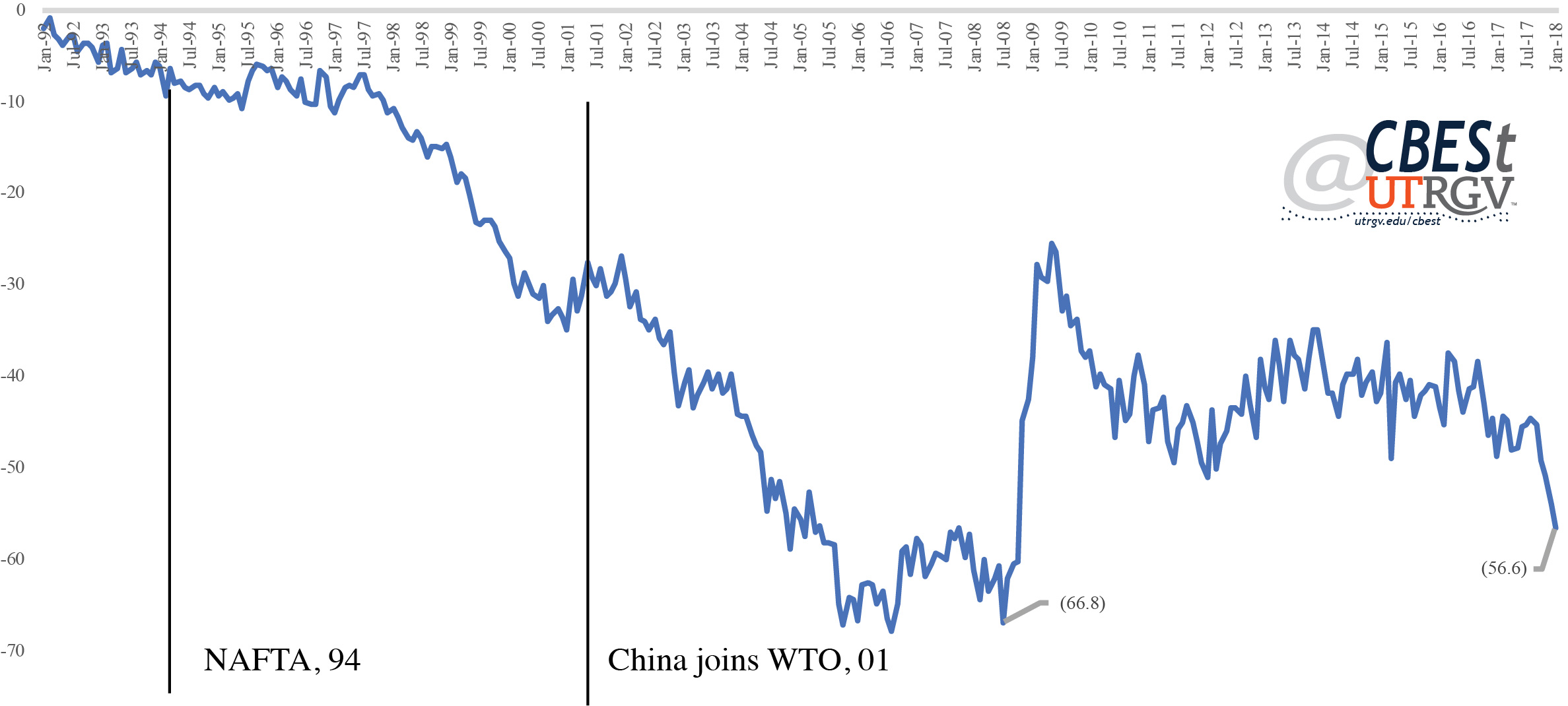

Figure 1 displays the US trade balance since 2001. It has been negative for the whole period and has fluctuated between 2.5 percent (2016) and 5.5 percent of GDP (2005). In 2024 this number was 3.1 percent of GDP, very close to the minimum. While unfair trading practices do happen (e.g., ignoring US property rights by some countries), and these can affect bilateral trade balances, a crucial factor often missing from discussions about the persistent US trade deficit is the low US saving rate relative to the level of US investment. A negative trade balance is necessarily a consequence of national savings being lower than domestic investment.

By definition, national savings is the sum of private and public (government) savings. Governments can run fiscal deficits, meaning that they spend more than they collect in taxes, which leads to the accumulation of public debt. A fiscal deficit is commonly known as the “budget deficit” (budget deficit:

government’s saving is actually negative), which under some circumstances can lead to a trade deficit. This scenario has been referred to as the “twin deficits,” where a government’s budget deficit causes (or is a significant factor in producing) a trade deficit

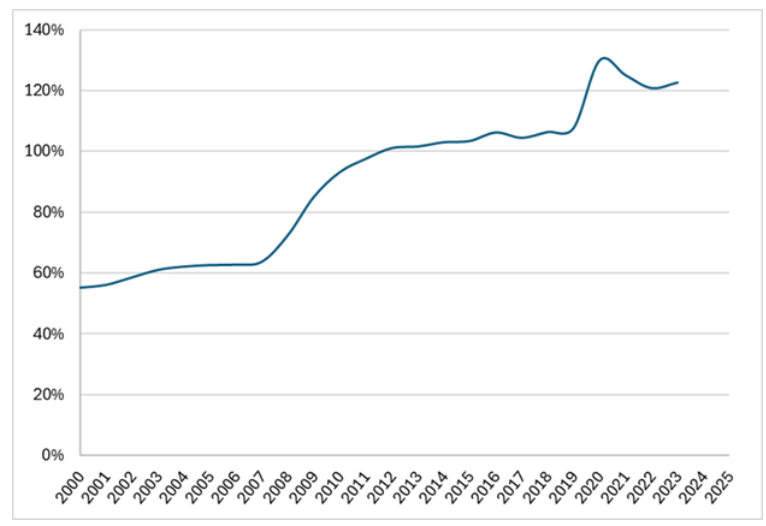

Figure 1 also illustrates the US budget deficit as a percentage of US GDP since 2001, showing how much the government needs to borrow each year to cover its expenses. Note that 2001 was the last year the US had a fiscal surplus. It is also apparent that in recent years, the budget deficit dwarfs the US trade deficit. A persistent budget deficit can represent a problem because it means that the government is growing its debt as a percentage of GDP (see Figure 2, where US public debt in 2023 is a staggering 123 percent of GDP), which after some point (not clear where is that threshold, which is different for different countries for a host of reasons) might be unsustainable.

Figure 1: The Twin Deficits: The US Budget Deficit and the US Trade Deficit

Sources: Gross Domestic Product [GDP], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https://fred.stlouisfed.

org/series/GDP, February 12, 2025. Budget Deficit, US Department of Treasury. National deficit data. Retrieved from https:

//fiscaldata.treasury.gov/americas-finance-guide/national-def.: US Census Bureau and US Bureau of Economic Analysis, Trade

Balance: Goods and Services, Balance of Payments Basis [BOPGSTB], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis.

Going back to trade, classical economic theory illustrates that negative trade balances in the present will imply positive trade balances in the future. Essentially, trade deficits mean borrowing from the rest of the world, and in periods in which the country repays those claims, it runs a trade surplus. But there is one special circumstance that allows the US to run permanent trade deficits (at least of “moderate” size) and that is not available to other countries. Since the US dollar is used as reserve currency worldwide, when other countries receive dollars in exchange for their goods, instead of buying American goods and services with those assets, they decide to keep those green pieces of paper as a store of value (or to conduct international transactions between foreign countries), so that the US can permanently run a negative trade balance every period.

These are actually good news for Americans in that we obtain real goods and services from the rest of the world in exchange for green pieces of paper (other assets can also be used, but that possibility is available for other countries also; what matters is the possibility of paying for foreign goods and services with an intrinsically worthless asset called a dollar, not backed by gold or anything else). If the citizens and governments of other countries stop using the dollar as a store of value (or use it less than currently), trade surpluses would be more likely for the US. In summary, a trade deficit can result from a budget deficit: too much government spending relative to taxes collected, not because other countries are taking advantage of the US (which can happen in individual cases or industries). Some countries might be engaged in unfair trade practices. But a bilateral trade deficit is not evidence of this; in general, it is an irrelevant figure. The aggregate trade balance of the US can also be negative because of the special place of the dollar in the world monetary system.

Figure 2: US public debt as percentage of GDP

Sources: Gross Domestic Product [GDP], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https://fred.stlouisfed.org/ series/GDP, February 12, 2025. Total Public Debt, US Department of the Treasury. Fiscal Service, Federal Debt: Total Public Debt [GFDEBTN], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/GFDEBTN, February 14, 2025

Effects of Tariffs on Product Markets and Consumers

Policymakers typically face two competing issues when enacting a tariff policy. On the one hand, it may stimulate import competing industries, boosting domestic supply, and generating new jobs. On the other hand, tariffs can yield an increase in prices (and inefficiency as domestic firms protected by tariffs spend resources on rent seeking to keep tariffs in place rather than improve productivity). So, the net effect of the tariff policy depends on the size of each dimension. However, typically, trade liberalization in countries, when accompanied by reform policies, tends to be accompanied by economic growth, a decrease in the price of goods, and improved productivity in the exporting sector. Additionally, there is a consensus that imposing a tariff policy on a specific product leads to higher prices for this product and other related goods and services. It is worth noting that the time horizon also matters in assessing the effect of higher trade barriers. It is for this reason that President Trump, when announcing his tariff policy, acknowledged that ``there may be a little pain for Americans in the short term.”

As a concrete example, between 1981 and 1984, there was a trade restriction of Japanese automobiles to the US. This policy led to an increase in the price of automobiles for American consumers. With a US-Japan trade agreement in the long run, Japanese manufacturers invested in the US, and nowadays, the US has a vibrant automobile industry. Other scholars, such as Meredith Crowley, Professor of Economics at the University of Cambridge, have suggested that other forms of direct government support may have generated more substantial support for the US industry than trade barrier policies (Dharshini, 2025).

Tariffs act as taxes and, like most government interventions, distort free exchanges between demanders and suppliers of goods and services. The tax burden distribution depends on the price elasticity of consumers and suppliers in the market. While in the short-term, some suppliers may be reluctant to pass the resulting additional cost to consumers, they tend to do it gradually. As Meredith Crowley put it, “Once you realize the tariff is in place permanently, the manufacturer realizes everyone’s going to have to pay it, and they gradually raise their prices” (Dharshini, 2025, n.d). Since tariffs are levied on goods rather than services, and lower-income individuals tend to buy more goods, they bear a heavier tariff incidence. Non-economic rationales for supporting tariffs do not erase the economic costs and potential inflationary effects of tariffs. Whether the primary motive is economic or geopolitical, without well-calibrated tariff policies, the inefficiencies and welfare losses remain.

Effects of Tariffs on Exchange Rates

One final variable that has not yet been discussed is the exchange rate between the US dollar and the Mexican peso and, in general, between the US dollar and any other currency or basket of currencies in the world. An indirect effect of trying to protect US industries (before any retaliation by other countries) is that foreigners find it more difficult to obtain dollars, which are required for paying for American goods and services. In terms of supply and demand for dollars, the supply decreases when tariffs are imposed and this leads to an appreciation of the dollar (the dollar becomes more expensive).

An appreciation of the dollar in itself (in the absence of considering that tariffs make imports more expensive) is good for American consumers as it makes imports cheaper. But it is not good news for American exporters. That is, the exchange rate appreciation induces American goods and services to become more expensive to foreigners, something that tends to increase foreign imports in the US and decrease American exports, arguably the opposite of the intended effects of protecting domestic industries via tariffs. Put differently, generalized tariffs on imports appear to give an advantage to exporters but produce an exchange rate effect that affects them negatively.

While a unilateral increase in tariffs leads to an appreciation, in a trade-war scenario, the ultimate effect on the exchange rate is hard to forecast as it also depends on the response of the other countries and on which countries end up affecting the most in terms of foregone output. What is clear is that the volume of trade decreases, and all consumers and producers in all countries end up paying the tariffs imposed by other countries, and everything becomes more expensive, leading to misallocation of resources and less specialization, thus producing an aggregate decrease in welfare.

Finally, one additional undesirable effect for the US is that a full-blown trade war could induce more countries to organize efforts to replace the dollar with something else (e.g., BRICS), something that is arguably not in the best interest of Americans for reasons specified above.2

Implications of a Trade War on Unauthorized Migration

In 2023, approximately 80 percent of Mexican exports and 78 percent of Canadian exports went to the US. From the US perspective, about 15 percent of total imports came from Mexico and 14 percent from Canada (O’Neil and Huesa, 2025). The sum of exports plus imports as a percentage of GDP is a measure of the degree to which each economy depends on trade. In 2023, Mexico’s total exports were worth $603 Billion (B), while imports were worth $528B. Since Mexico’s GDP was $1,790B, exports plus imports were 63 percent of the value of the Mexican GDP. In the case of Canada, the figures for the same year were respectively $574B, $533B, and $2,140B, for exports plus imports representing 51.7 percent of GDP. In contrast, for the US, these figures are $1.86 Trillions of exports, $3 Trillions of imports, and a GDP of $27.72 Trillions, for exports plus imports representing only 17.5 percent of US GDP.3 These numbers clearly show that Mexico and Canada are more dependent on trade with the US than the US is on trade with those countries.

Economic shocks have effects on immigration flows. There is significant migration from Mexico to the US of both the legal or authorized (family-based and jobs-based) type and illegal or unauthorized type. Unauthorized migration, in particular, is responsive to the business cycle, increasing during US economic booms and decreasing during Mexican booms, driven by several “push” and “pull” factors of immigration.4 A full-blown trade war would harm all involved countries, but it would be particularly damaging to Mexico and Canada due to its significant exposure to the external sector and, more importantly, due to the volume of trade with the US. If the US imposes general tariffs on Mexican imports and other factors remain constant, the incentives to emigrate to the US without authorization would increase. The bigger the gap between US GDP growth and its Mexican counterpart (or the worse the recession in Mexico is), the larger the expected unauthorized migration flows to the US. The Trump administration has already shown that enforcement actions will be used to curb unauthorized immigration. However, within this type of immigration, the overstaying of temporary permits (e.g., tourist visas) has historically been hard to detect as the entry of these foreigners into the US is legal. According to Warren and Kerwin (2017), the percentage of over-stayers within the unauthorized population (as opposed to entries without inspection) increased from 29 percent in 1995 to 66 percent in 2014.

A few tariffs in certain sectors are unlikely to cause significant labor movements if the Mexican economy grows at a rate close to that of the US, especially if the other countries refrain from escalating. However, a full-blown trade war would reduce overall trade and likely deliver a more significant blow to the very open Mexican economy, leading to increased unauthorized migration to the US. These expected effects are inconsistent with the Trump administration’s objectives on unauthorized immigration: keeping unauthorized migration at a low level is incompatible with harming the Mexican economy and other source countries of unauthorized immigration.

Likely Scenarios for The Rio Grande Valley

The Rio Grande Valley (RGV) depends on trade with Mexico, facilitated by the ports of Roma, Brownsville, McAllen, Hidalgo, Progreso, and Rio Grande City. Many local businesses rely on goods from Mexico. Exports from the Maquiladora industry, which assembles goods in Mexico using parts from the US, generate jobs for trucking, warehousing, and logistics companies in the RGV. Several retail stores in the two major metropolitan areas, Brownsville-Harlingen and McAllen-Edinburg-Mission, benefit from Mexican shoppers who live across the Texas border. Increasing tariffs on imports and exports could generate adverse consequences, including manufacturing and supply chain disruption, trade, job losses, and economic slowdown. RGV farmers, who export citrus and other agricultural products to Mexico, could face reduced demand if Mexico imposes retaliatory tariffs. The burden on farmers can be significant if the tariff dispute includes additional costs of seeds, fertilizers, and agricultural equipment. If farmers and retailers can’t pass on extra costs to their customers or receive other support from the government, they will exit the market.

Concluding Remarks

The current US administration has positioned tariffs as a central tool of economic and political leverage. While tariffs can counteract unfair trade practices, their indiscriminate application poses significant economic risks, potentially destabilizing not only the US economy but also key trade partners like Mexico and Canada. These nations, heavily reliant on trade with the US, would face severe economic repercussions under an extensive tariff regime.

Strategically, the threat of tariffs can serve as a bargaining tool to secure concessions on issues such as border security, control of illicit substances (e.g., fentanyl), and deportation agreements. However, broad-based protectionism can lead to unintended consequences, including currency appreciation that undermines US export competitiveness. Additionally, economic strain in Mexico due to restrictive trade policies may exacerbate unauthorized migration, contradicting US immigration objectives.

Economically, addressing trade deficits through tariffs is misguided, as bilateral trade balances are not a primary macroeconomic concern. More pressing is the US budget deficit, which poses a greater risk to financial stability. Furthermore, an all-out trade war could accelerate global efforts to reduce reliance on the US dollar, diminishing American economic influence.

The administration's tariff strategy appears to be more about political leverage than economic confrontation. While targeted tariffs against unfair trade practices—such as intellectual property violations—may be justified, widespread protectionism risks economic instability and geopolitical backlash. Perhaps a measured and strategic approach to tariffs is the most pragmatic course of action.

____

Maroula Khraiche is an Associate Professor of Economics at the University of Texas Rio Grande Valley.

Armando Lopez-Velasco is an Assistant Professor of Economics at the University of Texas Rio Grande Valley.

Jean-Baptiste Tondji is an Associate Professor of Economics at the University of Texas Rio Grande Valley.

Endnotes

- See, e.g., BBC News and BBC Central America on February 3, 2025.

- BRICS is an intergovernmental organization consisting of ten countries—Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa, Egypt, Ethiopia, Indonesia, Iran, and the United Arab Emirates.

- Data on exports and imports are available at The Observatory of Economic Complexity at https://oec.world/en. GDP figures available from World Development Indicators, available at https://databank.worldbank.org/.

- Some recent evidence of the response of unauthorized immigration flows to push and pull factors on immigration is found in Lopez-Velasco (2025). Lee (1966) is the author who first describes the “push” and “pull” factors of immigration.

References

- Boak, J., Verza, M. & Gillies, R. (February 4, 2025). What did US get from deals to pause tariffs on Canada and Mexico? Not that much, observers say. [Text file] Associated Press. Retrieved from

- Dharshini, David. (February 10, 2025). The Debate: Do Trump’s tariffs mean the end of the post-war free trade world? [Text file]. BBC News.

- Head, Keith, and Thierry Mayer. (2019). Brands in Motion: How Frictions Shape Multinational Production.American Economic Review, 109 (9): 3073–3124.

- Lee, E. (1966). A theory of migration. Demography, 3(1), 47–57.

- Lopez-Velasco, A.R. (2025) On the design of an optimal immigration policy. Economic Inquiry, 63(1), 47–97.

- Wile, Rob. (February 6, 2025). Trump detests the US trade deficit. Here’s what it means. [Text file]. NBC News.

- O’Neil, S. K., & Huesa, J. (February 5, 2025). What Trump’s Trade War Would Mean, in Nine Charts. Council on Foreign Relations.

- Reuters (January 23, 2025). LIVE: WTO Director-General Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala discusses tariffs at Davos.[Video file].

- Stevis-Gridneff, M., Swanson, A., & Romero, S. (February 3, 2025). How Could Trump’s Tariffs Affect the US, Canada, and Mexico? [Text file]. New York Times.

- Warren, R., & Kerwin, D. (2017). The 2,000 Mile Wall in Search of a Purpose: Since 2007, Visa Overstays have Outnumbered Undocumented Border Crossers by a Half Million. Journal on Migration and Human Security, 5(1), 124-136.Migration and Human Security, 5(1), 124-136.

Fall 2023 v19, n1

A snapshot of Immigration Flows into the US

Armando R. Lopez-Velasco

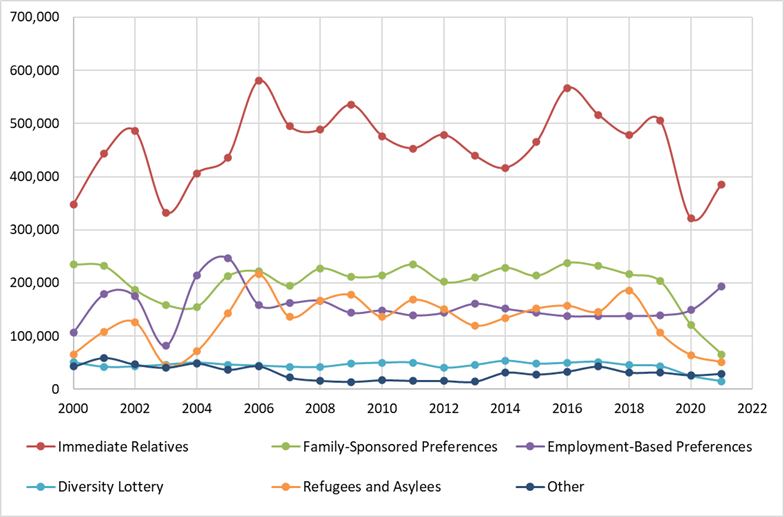

The US is a rich country to which many people from developing countries would like to migrate to. The opportunities to migrate are restricted to people who fall into certain categories: relatives of US citizens (with priority given to immediate relatives of American citizens but there are permits to other relatives under “family-sponsored” preferences like siblings of American citizens), workers with certain skills (mostly classified as high-skilled), permits for refugees and asylees; and finally there is a “diversity” lottery where people from countries with low rates of immigration to the US can apply.

The number of permanent resident permits given in the US for the period 2000-2021 are shown in figure 1. For the years 2000-2019, which do not include the last 2 years as they can be atypical due to the pandemic, approximately 65% of all the permanent residence permits were allocated towards family-based immigration, which represents an average of about 680,000 permits per year. Skill-based categories represent about 154,000 permits per year (almost 15%), refugees and asylees were given an average of 135,000 permits (almost 13%) while about 47,000 (4.5%) permits were allocated to the diversity lottery. Finally, about 3% were given for other categories.

Fall 2023 v19, n1 (ACCORDIAN menu starts here)

Figure 1. Permanent resident permits given by type of immigrant (2000 – 2021)

Source: Department of Homeland Security, Yearbook of Immigration Statistics. Various years. Available at: https://www.dhs.gov/immigration-statistics/yearbook

For people that do not have close relatives which are US citizens nor qualify for having special skills that would allow them to migrate to the US (e.g. a Ph.D. from an American University), there does not exist a mechanism that would allow them to come to the US to work legally either in a temporary or permanent way. For those individuals, the only way to come and work in the US is via unauthorized immigration, either in the form of crossing the border illegally (mostly through the Mexican border) and which is a very risky proposition that often involves paying large sums to human smugglers better known as “coyotes” as well as a very dangerous journey, or in the case of having a temporary visiting permit (i.e. a tourist-visa) by violating the terms of their stay (typically overstaying in order to work).

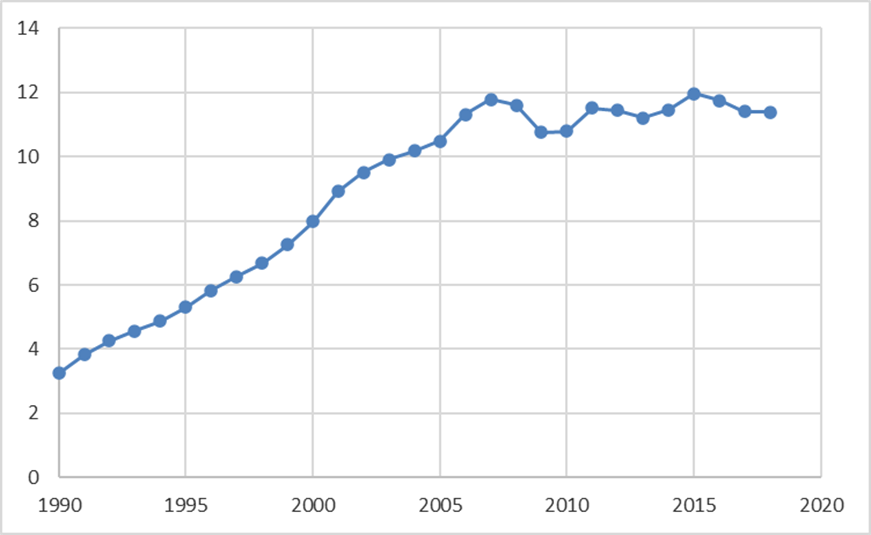

Figure 2 displays the stock of unauthorized immigrants for the period 1990-2018. This number starts at about 3 millions in 1990, and reaches a maximum of 12 millions in 2007 and 2015, with a decrease in 2008-2010 due to the effects of the housing crisis which dried up the demand for many jobs which unauthorized immigrants tend to occupy (e.g. construction workers) as well as the effects of the economic downturn. These numbers are in the aftermath of the legalization (amnesty) of 2.7 millions of unauthorized immigrants under the Immigration Reform and Control Act (IRCA) passed in 1986. IRCA also devoted more resources for border enforcement in an attempt to control future unauthorized immigration.

Figure 2. Unauthorized immigrants residing in the US, years 1990-2018 (Millions)

Source: Department of Homeland Security at https://www.dhs.gov/immigration-statistics/population-estimates/unauthorized-resident from 2005 to 2018. Years 1990 to 2004 inferred from growth rates constructed from estimates of the unauthorized population residing in the US by Warren and Warren (2013).

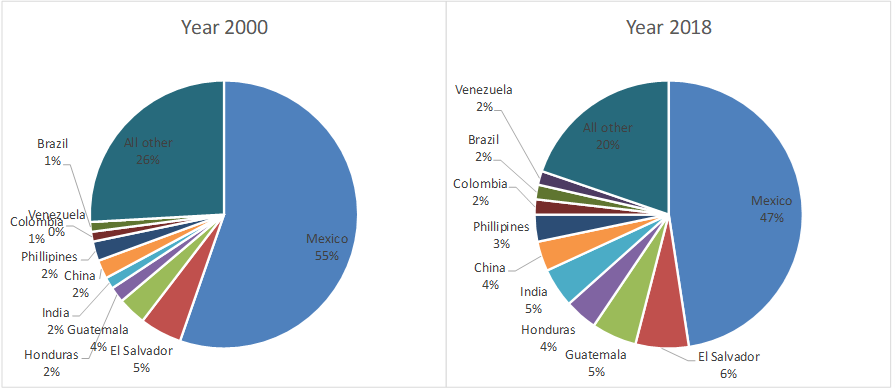

With regards to whom specifically are these unauthorized immigrants, figure 3 shows two snapshots of their country of origin for years 2000 and 2018. Mexican citizens represent the largest share, but such number has (steadily) decreased from 55% in 2000 to 47% in 2018. Central American countries have seen their shares increased over the same period: El Salvador from 5% to 6.4%, Guatemala from 3.4% to 5.4% and Honduras from 2% to 4%. At the same time, there are other countries who used to represent a small share of unauthorized immigrants but who now make a significant amount: China, India and Philippines accounted for about 6% of the total stock of unauthorized immigrants in 2000 but accounted for almost 12% in 2018 (most of their citizens via overstaying their visas rather than crossing the border without a visa). Similarly, Venezuela, Colombia and Brazil used to represent about 2% in 2000 but represent slightly more than 5% in 2018.

Figure 3. Origin of Unauthorized population residing in the US, 2000 and 2018

Source: Department of Homeland Security, Estimates of the Unauthorized Immigrant Population Residing in the United States available at https://www.dhs.gov/immigration-statistics/population-estimates/unauthorized-resident

Flows of unauthorized immigrants respond to “pull” (from the host economy) and “push” (from their country of origin) factors, as well as to the level of enforcement in the host country (see for example Orrenius and Zavodny (2013) and the references therein). High growth and low unemployment in the host economy are factors that tend to attract immigrants, while low growth in the sending economies, high unemployment and political instability in the sending economies are factors that tend to increase the supply of immigrants, everything else constant. For these reasons, the flow of unauthorized immigration is to be thought of as “equilibrium” migration flows which adjust in response to these forces.

In the case of family-based migration flows, since the US laws are such that there is no limit to who can come in the form of immediate relatives (parents, natives and children of American citizens), it implies that they are also equilibrium migration flows. Skill-based immigrants may or may not be an equilibrium flow in the sense that there is a limit in the number of high-skilled immigrants that can come to the US in a given year and that number is typically exhausted every year (thus the short side of the market would determine skill-based immigrants flows), while the case of refugees is a category that the US decides for diplomatic reasons in response to conflicts and international crisis/disasters.

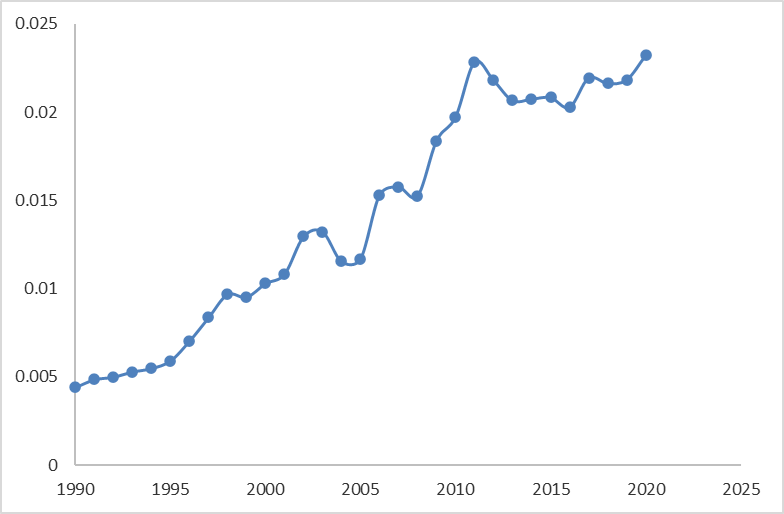

Figure 4. Border Patrol Budget as % of GDP

Source: US GDP: World Development Indicators, series NY.GDP.MKTP.CD at https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators#. Data on Budget of the Border Patrol from American Immigration Council, available at https://www.americanimmigrationcouncil.org/research/the-cost-of-immigration-enforcement-and-border-security.

Figure 4 illustrates that expenditure in enforcement, as captured by the US Border Patrol budget for the period 1990-2021, has been steadily increasing from almost .005% of GDP in 1990 to almost .023% of GDP in 2021. Yet unauthorized immigration kept increasing for much of this period until the housing crisis hit in 2008. Precisely because unauthorized migration responds to different forces, for all practical purposes bringing unauthorized immigration to 0 is impossible to achieve as there are real costs of enforcing the border and there are other variables that enter the decision whether to migrate or not in an unauthorized way, in addition to moral issues and diplomatic relations.

A possible amnesty for unauthorized immigrants has cost and benefits that are hard to quantify. Among the benefits, one can expect higher rates of income taxes paid by immigrants (though many do pay income taxes via an ITIN number[1]) from having a legal status; better allocation of talent as currently those immigrants tend to concentrate in certain industries for which a job doesn't require a social security number (e.g. construction workers, gardeners, domestic workers, etc.) as opposed to working in the sector where their productivity is highest and which would also lead to higher tax revenue; and there's also the human benefit that there are many families in the US where some of the members have legal status but some others do not. On the cost side, unauthorized immigrants do not qualify for most government transfers and so any amnesty would likely impact those costs. Similarly, unauthorized immigrants currently do not have social security benefits (even though some of them do pay social security taxes by means of an ITIN number) which could change under a possible amnesty. Also, as Orrenius and Zavodny (2013) have argued, IRCA lead to more legal immigration since the current system favors family-reunification. So, after gaining legal status, many of the legalized immigrants through IRCA were able to petition for their relatives once they became US citizens. Another point of contention is the right to vote that immigrants might obtain if they choose to become citizens (typically after having at least 5 years of permanent residence). Finally, there's an expectation channel where a current amnesty could lead to an expectation of a future amnesty as this arguably happened with IRCA, and hence in the absence of other enforcement measures and some form of temporary/guest worker program (discussed later), continued unauthorized immigration could be the result. Hence the political hot-potato that is any possible amnesty.

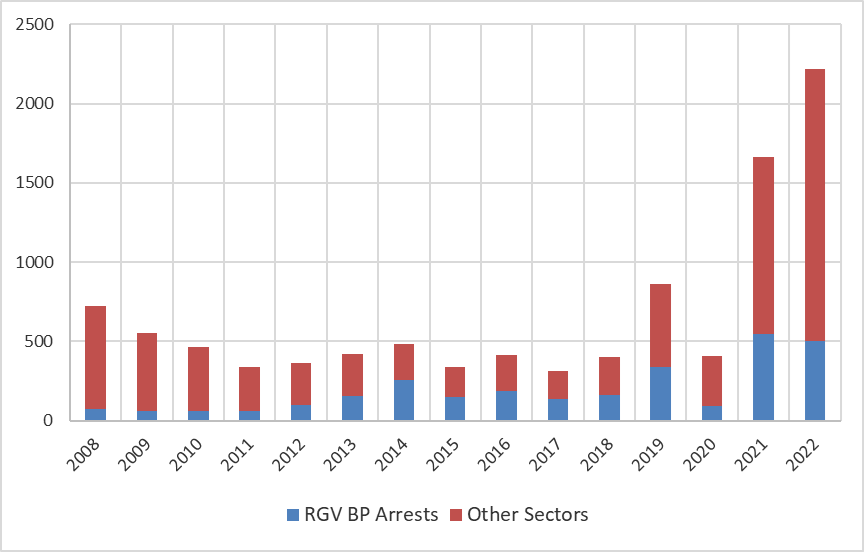

Arrest Data

Arrest data offers an interesting snapshot of who comes to the US in an unauthorized way. Figure 5 shows the number of arrests by the border patrol along the Mexican border, starting in 2008 as available from the Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse (TRAC) at Syracuse University. Starting in 2008, these numbers stayed below 500,000 arrests per year until 2019 which saw 860,000 arrests, then decreased during 2020 when countries closed borders and much of the economic activity was restricted during the early stages of the COVID pandemic. Finally, 2021 and 2022 have seen these numbers skyrocket to 1.65 and 2.2 million arrests respectively.[2]

The border Patrol divides the border with Mexico into 9 sectors. Five of these are located in Texas, which are Rio Grande Valley (RGV), Laredo, Del Rio, Big Bend and El Paso sectors. The other sectors covering the border with Mexico are Tucson, Yuma, El Centro and San Diego. Figure 5 also shows how many of the annual arrests took place in the RGV Sector.

From 2008 to 2011 The RGV sector had between 10 and 20% of all the arrests in the Mexican border. Starting in 2012 the RGV has become the sector with the most arrests, suggesting that there are more attempts to cross through this sector. Indeed, more than 52% of all the arrests during 2014 took place in the RGV. More recently, in 2021 the RGV share of arrests was 33%, which corresponds to about 549,000 arrests in 2021.[3]

Figure 5. Border patrol arrests in the Mexican border (1000’s)

Source: Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse (TRAC) at Syracuse University, available at https://trac.syr.edu/phptools/immigration/cbparrest/ . Total arrests for year 2022 available at https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/stats/cbp-enforcement-statistics . Number of arrests at Rio Grande Valley sector for year 2022 are a projection from the observed numbers from TRAC for 2022 arrest numbers until July of 2022.

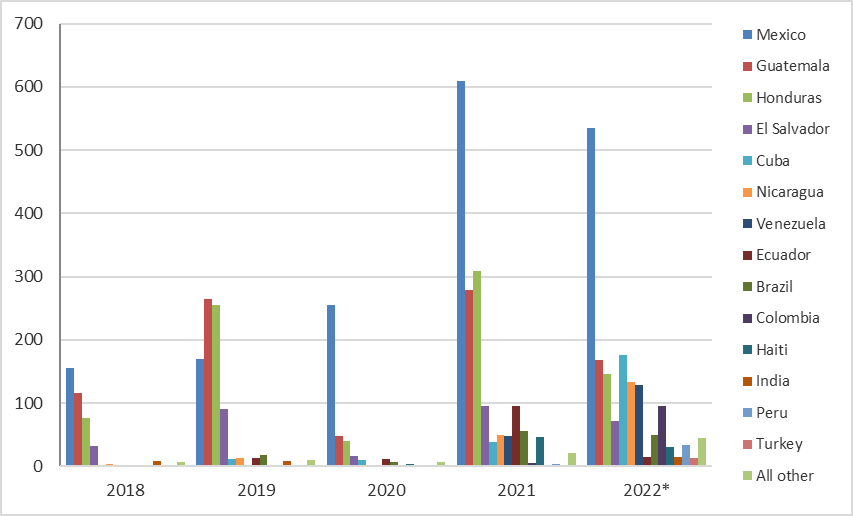

Figure 6 shows the countries of origin of the people most recently arrested by Border Patrol Officers, starting in 2018. In previous years, most of these unauthorized immigrants used to come from Mexico, Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador. Starting in 2021, a significant share of those arrests corresponds to individuals from other countries. In particular, other Central and South American countries including Cuba, Nicaragua, Venezuela, Ecuador, Brazil, Colombia, Haiti and Peru represented less than 2% of the arrests in 2018 when combined (and also in previous years, not shown), but lately those countries represent 20% of the arrests in 2021 and 40% of the arrests in 2022 (with data until July of 2022). There are also distant countries that historically were not represented among the arrested at the southern border, including people from India (14,826 arrests from January to July of 2022), Turkey (12,562), Romania (5,455), Georgia (4,728), Russia (3,987), Uzbekistan (2,755), Senegal (2,237), Bangladesh (1,790), Ghana (1,751), Angola (1,455) and China (1,244), among many others.

At this level of generality and without more data it is impossible to disentangle the specific reasons for why the recent increase in arrests and which presumably implies both a higher number of people arrested (as there is a possibility of attempting to cross multiple times) and a larger pool of people attempting to cross in an unauthorized way (some of which are successful and of course do not get counted in arrest data), but a few reasons are easy to identify. First, the pandemic affected countries in unexpected and asymmetric ways (not all sectors were equally affected) and thus lack of opportunities in the sending countries might have precipitated at least some of this increase. Second, the timing is also consistent with the change of administration in the US. There might be a perception by immigrants that the Biden administration might be less inclined to expel immigrants as compared to the Trump administration (though the Biden administration kept using title 42 to quickly expel immigrants attempting to obtain asylum in the US until May 11th of 2023).[4] The evidence from both old countries and the newer countries comprising a significant number of arrests at the southern border also suggest either an expectations channel, or perhaps diffusion of know-how about how foreigners can come through Mexico in order to attempt to cross into the US.

Figure 6. CBP arrest data by country of origin 2018 -2022* (Thousands)

Source: Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse at Syracuse University, available at https://trac.syr.edu/phptools/immigration/cbparrest/ . Data for 2022 until end of July.

Finally, title 42 which started in March of 2020, resulted in many people sent to Mexico during the pandemic, and this in turn created incentives to repeatedly attempting to cross into the US. Hence it is possible that the numbers for 2021 and 2022 are much more inflated than previous years in terms of counting aliens attempting to cross (as opposed to counting number of arrests). It is possible to estimate the number of aliens apprehended from the data on repeated arrests, which yields an estimate of slightly more than 1 million of aliens arrested in 2021, a number still higher than the number of arrests (also overstating aliens arrested but probably less) in any previous year to 2021 and thus the increase in foreigners remains.[5]

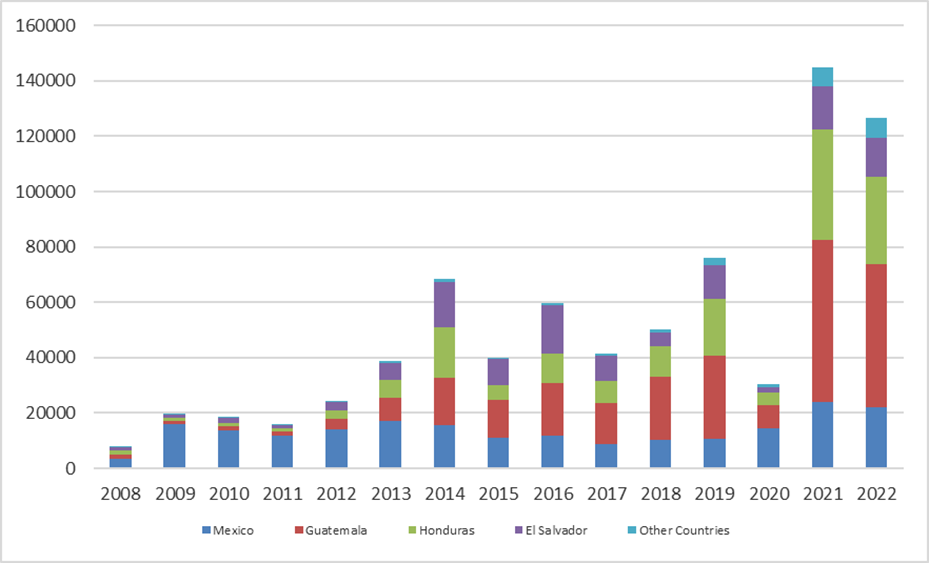

Figure 7 shows another recent phenomenon, the rise in the number of unaccompanied children coming to the US. In 2008 the total number of unaccompanied children was slightly above 8000, while in 2021 this number was almost 145,000. During the period discussed, more than 95% of them came from Mexico, Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador and for most of the period there was an upward trend. Recently (2021) the biggest shares came from Guatemala (40%) and Honduras (27%).

But why the increase in unaccompanied children? The situation of the sending economies could help explain some of these flows as the countries in Central America are relatively poor compared to other countries in the American continent, with a high poverty rate and violence. Then there is also incentives. In 2008 the US passed the William Wilberforce Trafficking Victims Reauthorization Act of 2008, which among other things created specific legal protections for minors traveling alone and which can produce a tension between the objectives of protecting the children from trafficking and the improved incentives for minor migrants to come unaccompanied precisely because of the better protection and possibility of staying at the US while their case is resolved.

Figure 7. Unaccompanied Children Arrested at Border by Origin

Source: Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse at Syracuse University, available at https://trac.syr.edu/phptools/immigration/cbparrest/ . Data for 2022 until end of July.

Since 2012, the majority of unaccompanied children have been arrested at the border through the RGV sector. For example, in 2021 in the RGV sector there were 76,284 arrests out of 144,873 minors arrested (almost 53%).

Often, minors turn themselves at the border to be arrested, as they are typically held in detention, and finally released to some family member in the US or to some sponsor after some days (perhaps months when detention centers are full). Of the minors which have been apprehended from 2014 to 2019, only 4% have been expelled (Hesson and Rosenberg (2021)). In addition, under title 42 (discussed below) during the pandemic minors could be expelled if traveling with their families, but not necessarily if they were traveling alone and which reinforces the incentive to split at the border -assuming they have someone on the US waiting for them. Finally, these numbers cannot show how many minors are abused, exploited and even die during the journey from other countries as only those that arrive and are arrested are counted.

Concluding Remarks

There are different types of immigrants and many different programs in the US that regulate immigration (directly in the case of legal immigration and indirectly via enforcement in the case of unauthorized immigration). This note attempts to present the state of immigration flows to the US and discusses some of the immigration challenges. Due to the complexity of the topic and in order to keep the discussion short, the note does not attempt to discuss comprehensive immigration reform.[6]

With respect to unauthorized immigration, addressing push factors (violence, lack of opportunities, poverty, etc.) is clearly important but it is something that depends heavily on the institutions and quality of the government of the sending countries. What a host economy like the US can control is the level of legal migration allowed into the country as well as the type and level of enforcement. An enforcement-only approach is unlikely to control unauthorized flows and is also likely to impose high human costs. There is possibly a better solution that could represent a win-win situation for the US and to many would-be unauthorized immigrants: the possibility of a guest or temporary worker program.

There are some advantages of a guest worker program when the alternative is unauthorized immigration[7]: it would allow for a way to come and work for a category of people that currently have no legal way of coming to the US. The stay is temporary as opposed to permanent as the current system ends up inducing unauthorized migration with a long stay (see Orrenius and Zavodny (2013)) due to the high costs of crossing.[8] Since by definition a guest worker program allows people only temporary in US soil, in a decade there could be a larger number of people who would benefit from working in the US temporarily as opposed to the same stock of people over many years under unauthorized immigration. Then those temporary workers would return to their home economies with some capital. Also, for national security issues, a guest worker program would be preferred over unauthorized immigration. Finally, other countries that are traveled during the journey to the US (e.g. Mexico) would also benefit from the existence of such program as many of the immigrants that are rejected in the US might end up in Mexican cities.

Some of the big winners of the status-quo are the criminal groups which charge significant amounts of money in attempts to smuggle people into the US or who kidnap or exploit foreigners while in transit to the border. Because of that, many potential immigrants would prefer to apply for a legal temporary worker permit, thus leading to some tax revenue (cost of the permit) plus some savings as compared to an enforcement-only framework in that the pool of potential unauthorized immigrants would be theoretically lower. Finally, the journey to come to the US would not be as dangerous as it is right now.

____

Armando R. Lopez-Velasco is an Assistant Professor of Economics at The University of Texas Rio Grande Valley.

Endnotes

- American Immigration Council, “How the United States Immigration System Works”, retrieved on 5/26/23. Available at https://www.americanimmigrationcouncil.org/research/how-united-states-immigration-system-works

- Kerr, Sari Pekkala & William R. Kerr (2011), “Economic Impacts of Immigration: A Survey”. NBER Working paper 16736, National Bureau of Economic Research Inc.

- Lopez-Velasco, Armando R. (2022), “On the Design of an Optimal Immigration Policy”. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4047652 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4047652

- Orrenius, Pia M. and Zavodny, Madeline (2012). "The Economic Consequences of Amnesty for Unauthorized Immigrants," Cato Journal, Cato Institute, vol. 32(1), pages 85-106, Winter.

- Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse at Syracuse University, available at https://trac.syr.edu/phptools/immigration/cbparrest/

- United States. Department of Homeland Security (2021). Yearbook of Immigration Statistics. Washington, D.C,: U.S. Department of Homeland Security, Office of Immigration Statistics, 2022.

Footnotes

[1] A social security number is needed in order to work in the US. In absence of it, immigrants can request an Individual Tax Identification Number (ITIN) for tax purposes.

[2] Number of arrests is not the same as numbers of aliens apprehended since some of them can do multiple tries in a calendar year if deported to Mexico. Still, when seen as a proxy, the number of arrests are indicative of a bigger pool of people trying to enter the US in an unauthorized way.

[3] In the months of January to July of 2022 there were 374,645 arrests in the RGV sector. The RGV share of total arrests up to that point in time was 22%.

[4] Title 42 was a law passed in 1944 which had never been used before and which gave authorities the power to expel people at the border in case of contagious disease, in this case used for the Covid pandemic. Hence even if some of those potential immigrants were claiming asylum, the US could quickly expel them at the border and not process those applications. In some cases, this resulted in quickly deporting them to their home countries, and in some other cases leaving them in Mexico. Eventually the Biden administration stopped applying title 42 to minors (January of 2021) as the CDC issued an order that title 42 was not to be applied to minor immigrants.

[5] Using TRAC data it is possible to estimate the number of aliens from statistics on the frequency of observations with specific number of arrests. In 2021 the estimated number of aliens is 1,040,695.

[6] For an analysis of what constitutes an optimal immigration policy and how different forces shape the demand for the different immigration flows, please see Lopez-Velasco (2022).

[7] The possible wage effects of immigration are ignored in this discussion since the alternative to a guest worker program is unauthorized immigration (as opposed to zero unauthorized immigration) and thus for a same pool of workers under each regime, the wage effects would be approximately the same under each scenario. Whether immigration affects wages of natives is an empirical question where the results are essentially mixed. See for example, the survey in Kerr and Kerr (2011).

[8] Orrenius and Zavodny (2013) argue that previous to the events of September 11 of 2001, unauthorized immigrants from Mexico would come to the US and work for a season, then go back home. After these events, an emphasis on national security at the border made crossing a more expensive and complicated endeavor. Since crossing back and forth became unfeasible, duration of the stay became much longer (mostly permanent).

Fall 2022 v18, n2

Taming Inflation: The Tradeoffs of Monetary Tightening

Maroula Khraiche and Andre Mollick

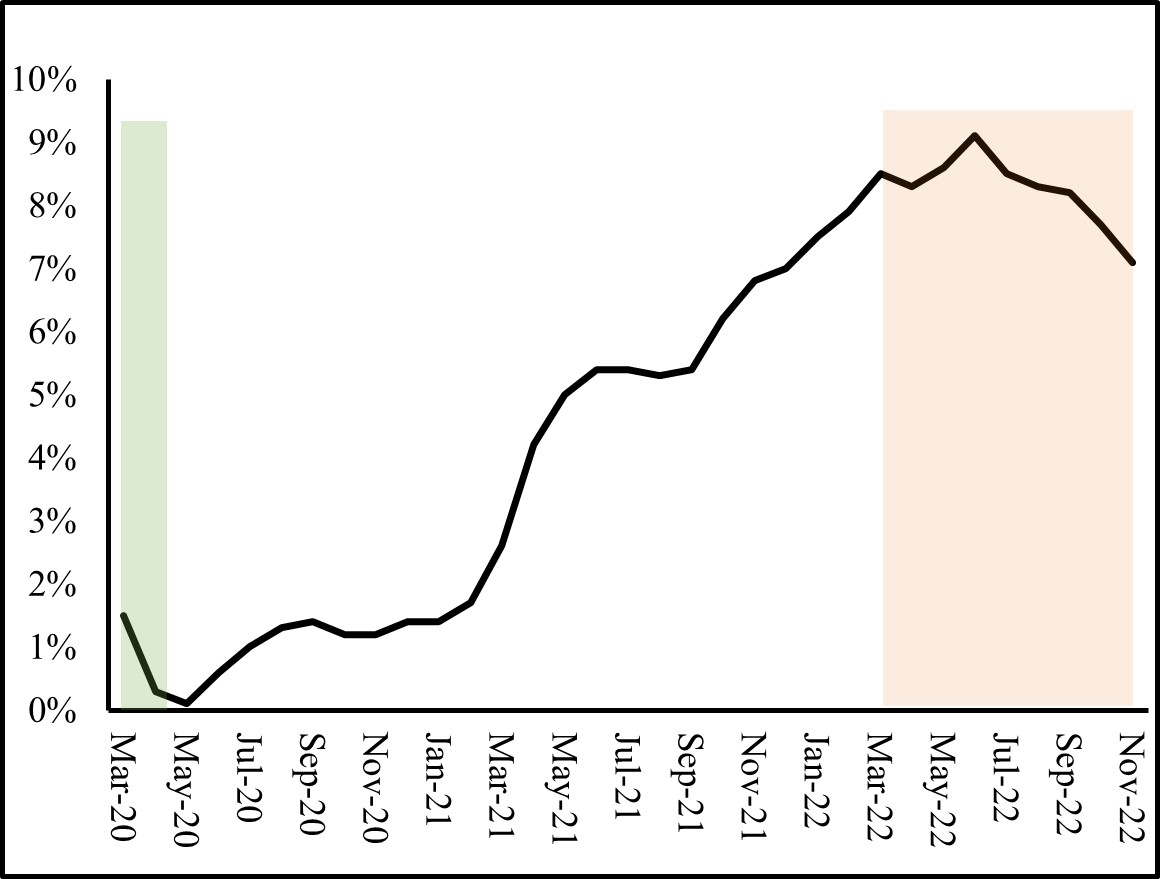

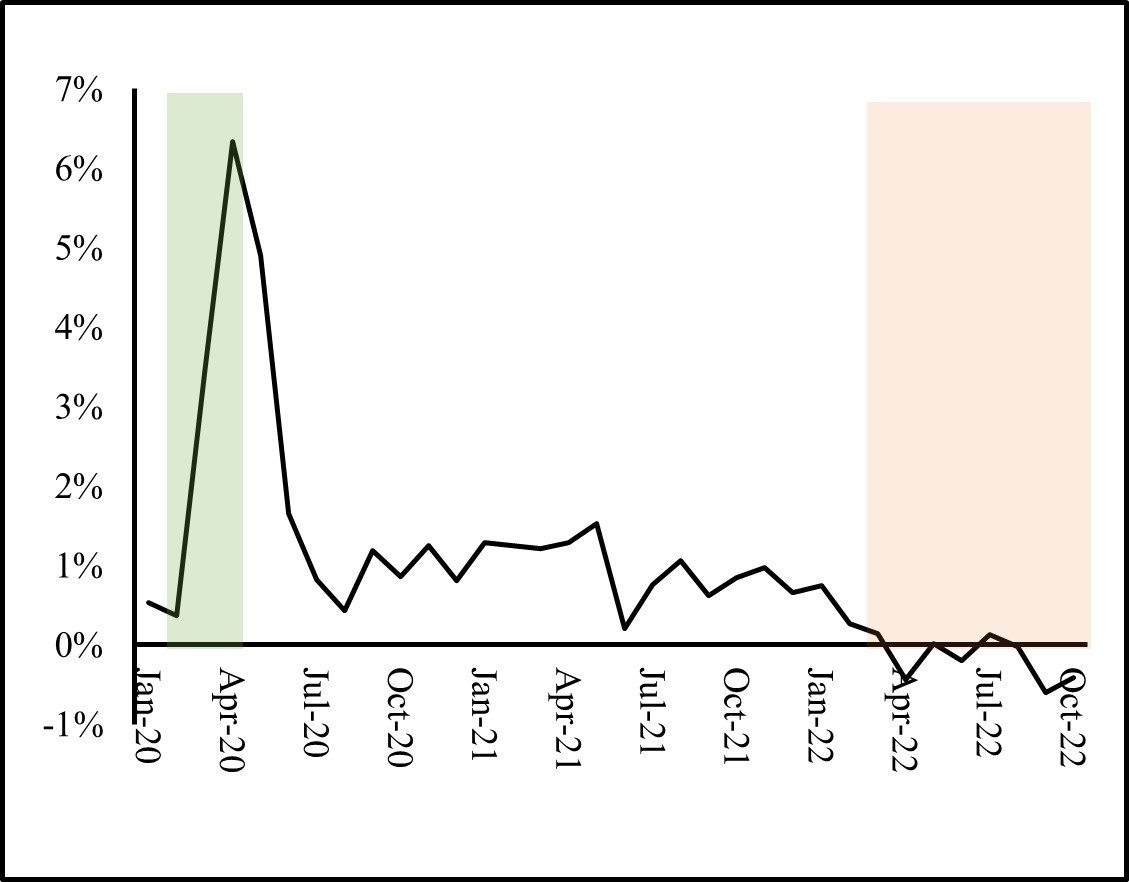

In the summer of 2022, consumers experienced the highest inflation rates in decades. In June of 2022, the Consumer Price Index (CPI), rose 1.3% compared to May, which implied a 9.1% increase over the past 12 months. The CPI is a measure of the average change over time in the prices paid by consumers for a basket of goods, therefore, changes in the CPI pin down inflation faced by consumers. In more welcome news released on December 12th, 2022, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) reported that the CPI rose only by 0.1% in November compared to the previous month. This implies that over the last 12 months, inflation was 7.1% . Nonetheless, this level of inflation is still higher than the 2% historically targeted by central banks. If fact, economists view such a high inflation rate as destabilizing. Panel (a) in Figure 1 depicts the fall and then sharp increase in the growth rate of the CPI (i.e., inflation) since the beginning of the pandemic until November of this year.

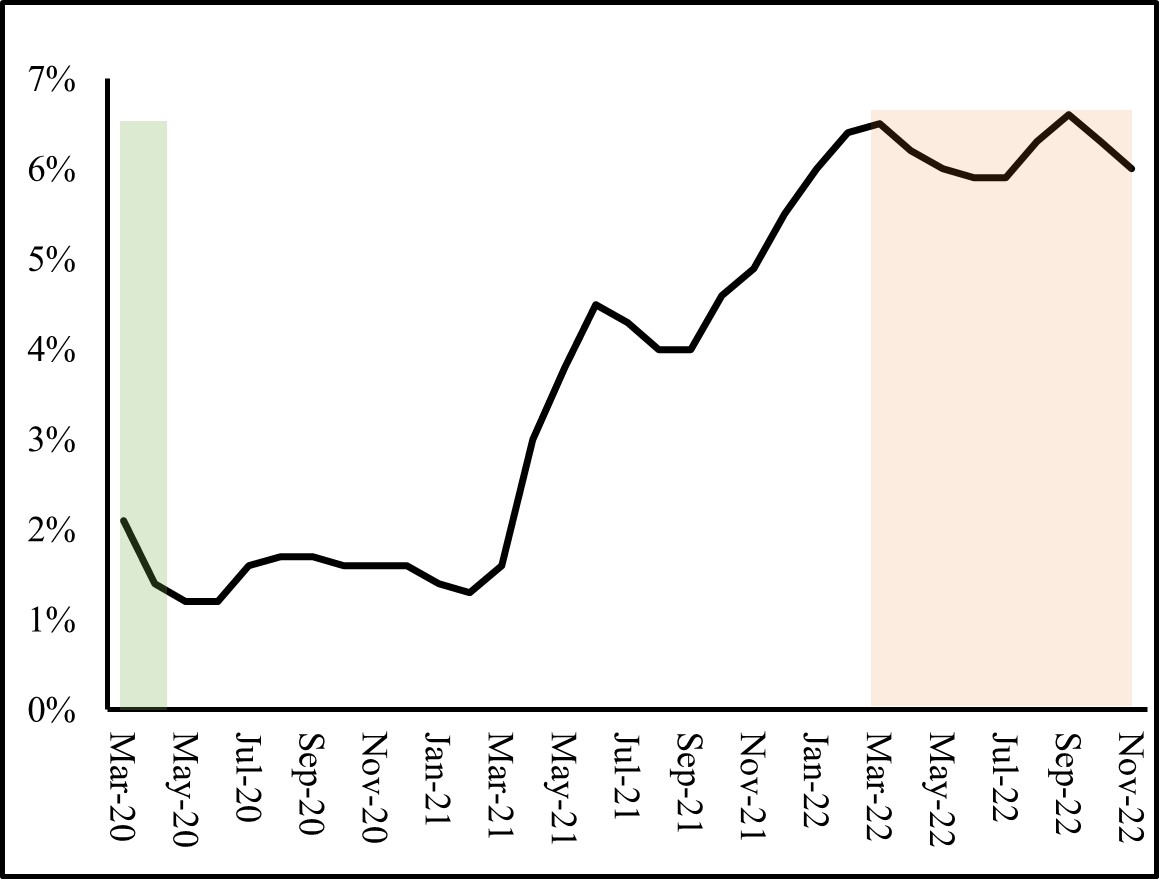

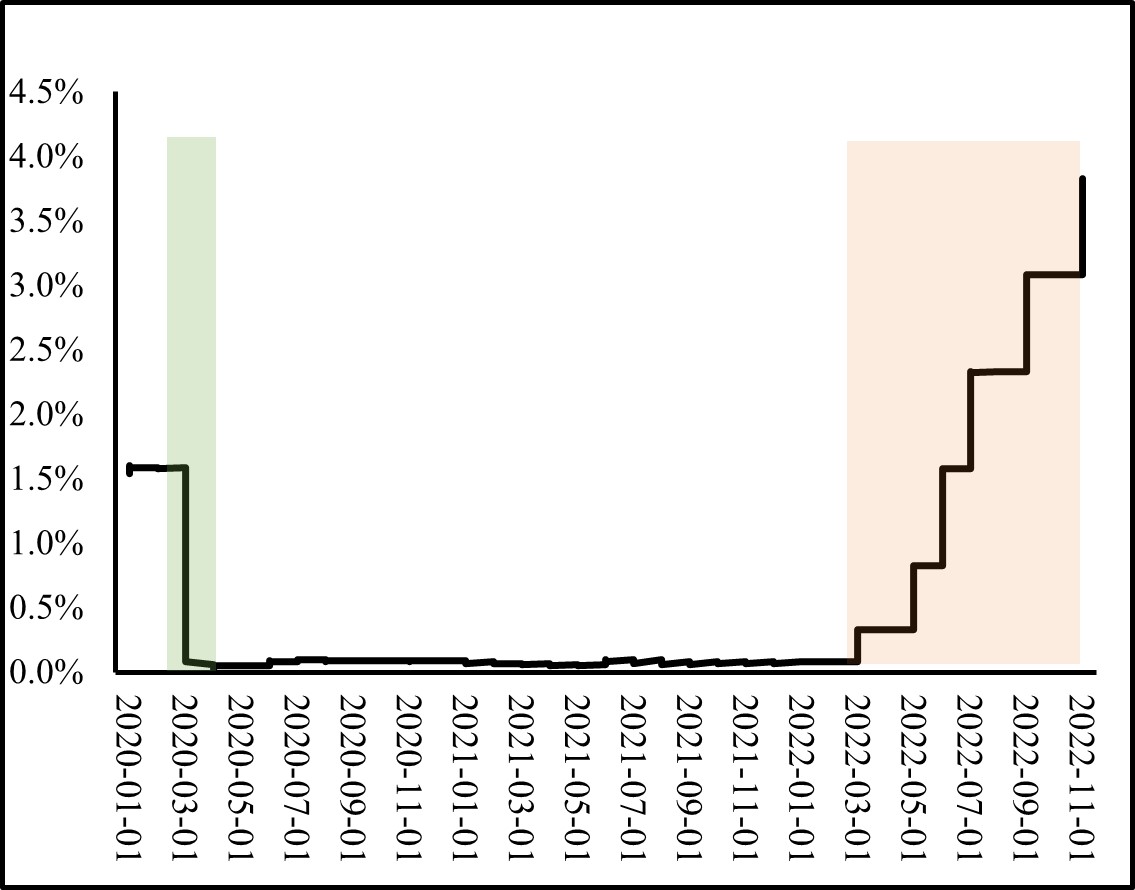

Another worrying sign is that inflation has exhibited a persistent upward trend over the past year. Initially, these inflationary pressures were thought to be transitory resulting from the imbalance between supply and demand created by the pandemic; elevated demand partially driven by extra funds households received from relief packages was met with shortages and supply chain interruptions. Furthermore, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine raised food and energy prices, which raised costs and added to the price pressures. Yet looking at the core inflation rate, which excludes food and energy prices, high and persistent trends in inflation are still detected. Over the past year, core inflation grew about 6.5% in the U.S. pointing to causes other than the rise in energy prices. Panel (b) in Figure 1 shows the increase in core inflation. With the economy still recovering from the pandemic and in hopes that the rise in prices would resolve as supply chain disruptions and pandemic fueled demand for goods dissipated, the Federal Reserve (Fed) was slow to respond, further fueling inflation. What’s causing this persistence in inflation? One explanation is the public’s expectations. Inflation tends to have momentum and as people expect higher prices, higher prices materialize. However, another predictor of future inflation is the growth of money. Money supply rose dramatically over the past two years as the Fed cut interest rates to near zero to stabilize the economy during the pandemic. Panel (a) in Figure 2 shows the steep rise in money supply measured as M2. According to the St. Louis Fed, as of May 2020, M2 consists of M1 plus small-denomination time deposits and balances in retail MMFs and M1 consists of currency, demand deposits at commercial banks and other liquid deposits, consisting of OCDs and savings deposits (including money market deposit accounts).

This report discusses the role policy may have played in fueling inflation and the role it is playing in taming it. Despite the focus on policy in this report, it is worth noting that the extraordinary economic shock of the pandemic has also had an effect on aggregate price and this effect has yet to fully disappear and may be even more important than policy.

Fall 2022 v18, n2

Figure 1: The Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers, Annual Percent Change

Green area indicates the Covid recession, orange area indicates the period of monetary tightening. Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics

(a) All Items

(b) All items less food and energy

Fiscal and Monetary Response

During the pandemic, both fiscal and monetary policy were used extensively to keep the economy afloat during this extraordinary health crisis. Fiscal policy is defined as the use of government revenue and spending in order to influence the economy. During the pandemic, expansionary fiscal policy amounted to $5 Trillion in stimulus and relief packages. The Coronavirus Preparedness and Response Supplemental Appropriations Act which passed in March, 2020, allocated $8.3 billion to state and local governments to fight the spread of the virus, fund research for a vaccine, and support efforts to stop the spread of the virus overseas. Families First Coronavirus Response Act (FFCRA) was also passed. FFCRA allocated $192 billion to help families who rely on free school lunches, aid small firms finance paid sick leave for those suffering from COVID-19, add $1 billion to unemployment insurance in states, and fund COVID-19 testing [1]. During the same period, the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act (CARES Act) allocated $2.2 trillion to help families and industries, established the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) and the Economic Injury Disaster Loan (EIDL) and contained additional funding for hospitals and COVID-19 testing [3]. In 2021, the Consolidated Appropriations Act allocated $900 billion (some of which was distributed as direct payments to households) and the American Rescue Plan paid out $1.9 trillion in various relief for firms and households [5].

Monetary policy is undertaken by the Federal Reserve (the United States’ central bank) which generally adjusts money supply and interest rates in order to achieve economic goals. During the pandemic, providing liquidity and ensuring the stability of the financial system and the economy were the focus of the Fed. Therefore, the Fed cut the Federal funds (FF) rate by 1.5 percentage points on March 3 and March 15, 2020. These cuts lowered the short-term FF rate to a range of 0% to 0.25% (see panel (b) of Figure 2). In doing so, the Fed reduced the costs of borrowing and freed up reserves for banks, ensuring ample liquidity when needed and encouraging banks to make loans. Cutting the interest rates is typically achieved by increasing money supply through bond purchases (see box below), therefore, money supply rose dramatically in 2020 and 2021.

Another policy tool that the Fed has been employing since the Great Recession of 2007-2009 is Quantitative Easing (QE). At the time, cutting the FF rates to almost zero was not sufficient to spur on economic recovery. As a result, the Fed employed QE which involves the purchases of Treasury securities and mortgage-backed securities (MBS) using newly created electronic cash. Such purchases by the Fed boost banks’ reserves and lowers long term interest rates. On March 15, 2020, the Fed resumed the purchasing of large amounts of Treasuries and residential and commercial MBS initially to stabilize markets and then continued on with QE to provide further liquidity to markets [6]. In December of 2020, the Fed indicated that it would slow these purchases tapering its purchases further in December 2021.

Figure 2: Money Supply and Target Interest Rates

Green area indicates the Covid recession, orange area indicates the period of monetary tightening.

Source: St. Louis Fed

(a) Monthly M2, Monthly Percent Change

(b) Daily Effective FF Rate, Percent

FOMC and FF rate: The federal funds rate is a short-term interest rate at which banks trade the balances they have at Federal Reserve Banks with each other. Although the effective federal funds rate is determined in the market as banks with more liquidity negotiate lending rates with those seeking liquidity, this rate is also influenced by the Federal Reserve. If the Fed wishes to reduce the rate, the Fed instructs its traders to buy short term government bonds from banks, which in turn increases their liquidity as the bonds are exchanged for balances (these trades are termed open market operations). When banks have more liquid funds to loan out, this reduces the rate they charge each other for funds (in other words, the FF rate falls). Alternatively, if the Fed wishes to raise the FF rate, it will sell government bonds, reducing banks’ liquidity as they trade the bonds for balances. Open market operations are decided by the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) which meets eight times a year to determine a target for the FF rate. Although the FF rate is an interbank rate, it has the potential to influence the interest rates faced by consumers such as the prime rate, mortgages, loans, and savings rate. Intuitively, a bank’s lending rate will be related to the rate at which itself can borrow.

When should rates rise? When should they fall? Among other responsibilities, the Fed has a dual mandate set forth by Congress. The dual mandate is price stability and economic growth. If economic growth is in jeopardy, such as during a pandemic, the Fed will cut interest rate and provide necessary liquidity. If price stability is a concern, as is the case in 2022, the Fed will raise interest rates to reduce demand and tame inflation.

The Fight Against Inflation

For policymakers to fight inflation, some short-term economic pain and slowdown are inevitable in order to achieve long term economic stability. To minimize economic pain, the fiscal policy (set by Congress and the current Administration) must work in the same direction as monetary policy (set by the Fed). To that end, the Inflation Reduction Act was passed in 2022. The $437 billion spending package is expected to raise $737 billion in revenue and reduce net federal expenditures by $300 billion over the next decade, in hopes of reigning in the government budget deficit. Cutting the deficit can at times have the effect of dampening inflation if it reduces overall demand of goods and services and take pressure off the prices. Most of the additional revenue will be raised through a 15% corporate minimum tax rate and through prescription drug price reform allowing Medicare to negotiate the price of certain prescription drugs starting in 2026. Such a reform is welcome news given the high levels of the U.S. health care spending. However, the act packs the biggest punch in its environmental goals. $369 billion of subsidies and tax credits are to be allocated over the decade on electric vehicles (EV), renewable energy, carbon capture, and other climate change combating measures. For example, the IRA includes a subsidy of $7,500 for purchasing of EV for the lower end models and a requirement that 40% of battery components for EV be sourced from factories in the U.S. or its free trade agreement partners and that batteries be U.S. made by 2029. This is primarily to phase out Chinese components and minerals.

The IRA should have a favorable effect on cutting the U.S. greenhouse-gas emissions, but its effect on inflation will not be immediate. The Fed has the primary responsibility to reduce inflation. The Fed raised benchmark federal-funds rate six times this year (to a range between 3% and 4% from near zero, as can be seen in panel (b) of Figure 2). By raising borrowing costs and making it more costly to finance homes, cars, and business investment with higher interest rates, the Fed can curb demand for goods and services and relieve pressure off prices to further increase. In fact, the higher mortgage rates have slowed down the housing market. Housing starts and residential permits both fell on a national level.

The Fed is also hoping that a cooling down in the labor market can remove pressure off prices. And although showing some signs of loosening, labor markets remain tighter than they have ever been, with record rates of quits and job openings. Labor market tightness is sometimes measured by the number of vacant jobs compared to the number of workers available. A tight labor market favors workers. One reason for this tightness is that during the pandemic, labor market participation decreased due to many reasons such as early retirement, lack of childcare options, health concerns, and change in preferences. Another reason could be the change in the nature of available jobs during the pandemic. Labor market participation has not rebounded; therefore, the supply side of the labor market remains low. The demand for labor (vacancies) may decline as the Fed hikes interest rates. Indeed, initial jobless claims showed a slight increase signaling perhaps an increase in layoffs (but are still low enough to signaling a still strong labor market). Vacancies and new jobs have slowed down in September.

“Inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon” -Milton Friedman

As the Fed raises interest rates, reducing aggregate demand for goods and services, we expect a slowdown in economic growth and an increase in the unemployment rate. This is the price of stability: reducing aggregate demand with higher borrowing costs slows down economic activity and reduces employment but takes pressure off prices to further rise. Nonetheless, some economists would argue that even if the Fed does not raise rates, a slowdown might ensue as the expansionary effects of monetary (and fiscal) policy undertaken in the previous two years dissipate.

Regional Outlook

The changes taking place on a national level have had an effect on some sectors in Hidalgo County. Given its interest sensitive nature, the housing sector has experienced some shifts. Since the Federal reserve’s interest rate hike in March 2022, months in inventory has steadily increased reaching 3.9 in October of 2022, as can be seen in the Table 1. This is above the level seen last October when months in inventory was 2.4. Median home prices were stable (or slightly up) and single-family housing construction permits has steadily decreased since August. Permits, which are obtained before construction, are an indicator of future housing market conditions. This is to be expected as mortgage rates climb with the Fed’s raising of interest rates.

|

Table 1: Housing Market in Hidalgo County, Oct 21-22 |

|||||||

|

Month/Year |

Sales |

Dollar Volume |

Average Price |

Median |

Total Listings |

Months In |

Building Permit |

|

21-Oct |

325 |

74,992,709 |

230,747 |

200,000 |

861 |

2.4 |

512 |

|

21-Nov |

303 |

69,480,703 |

229,309 |

205,000 |

917 |

2.6 |

350 |

|

21-Dec |

362 |

84,411,566 |

233,181 |

218,750 |

828 |

2.4 |

375 |

|

22-Jan |

358 |

80,040,787 |

223,578 |

200,500 |

780 |

2.2 |

388 |

|

22-Feb |

350 |

77,934,240 |

222,669 |

205,000 |

731 |

2 |

290 |

|

Post Monetary Tightening |

|||||||

|

22-Mar |

409 |

100,166,775 |

244,907 |

215,000 |

716 |

1.9 |

385 |

|

22-Apr |

378 |

95,406,508 |

252,398 |

220,750 |

782 |

2.1 |

397 |

|

22-May |

408 |

102,359,297 |

250,881 |

228,150 |

845 |

2.3 |

402 |

|

22-Jun |

395 |

101,115,003 |

255,987 |

231,250 |

974 |

2.6 |

355 |

|

22-Jul |

338 |

84,694,764 |

250,576 |

230,000 |

1101 |

3 |

320 |

|

22-Aug |

383 |

95,084,719 |

248,263 |

220,000 |

1212 |

3.3 |

336 |

|

22-Sep |

324 |

79,412,623 |

245,101 |

228,500 |

1331 |

3.7 |

301 |

|

22-Oct |

323 |

77,484,495 |

239,890 |

225,000 |

1416 |

3.9 |

279 |

|

Average |

358 |

86,352,630 |

240,576 |

217,531 |

961 |

3 |

361 |

The labor market in the region remains fairly strong and stable with unemployment mirroring those before the pandemic levels (see Table 2). From June 2021 to June 2022, average weekly wages grew by 5.10% in Hidalgo County and by 7.80% in Cameron County. The wage growth has barely kept up with inflation over the past year in the region, although this is not evident on a national level where wages grew at a rate of slower than inflation implying a reduction in real wages, as reported in Table 3.

|

Table 2: Unemployment Rates For Select MSAs and Texas |

|||

|

|

Brownsville-Harlingen |

McAllen-Edinburg-Mission |

Texas |

|

Early 2020 levels |

|||

|

2020-Feb |

5.5 |

6.4 |

3.5 |

|

2020-Mar |

8.2 |

9.6 |

5.1 |

|

Post Monetary Tightening |

|||

|

2022-Mar |

6.1 |

7.0 |

4.4 |

|

2022-Apr |

5.9 |

6.8 |

4.3 |

|

2022-May |

6.0 |

6.9 |

4.2 |

|

2022-Jun |

6.9 |

8.1 |

4.1 |

|

2022-Jul |

6.8 |

8.0 |

4.0 |

|

2022-Aug |

6.4 |

7.6 |

4.1 |

|

2022-Sep |

5.8 |

6.7 |

4.0 |

|

Table 3: Employment and Wages (June 2021-June 2022) |

||

|

County |

12-month percent change in employment Total |

12-month percent change in average weekly wage Total |

|

Hidalgo |

3.7% |

5.1% |

|

Cameron |

3.9% |

7.8% |

|

Texas |

5.2% |

6.1% |

|

U.S. |

4.0% |

4.3% |

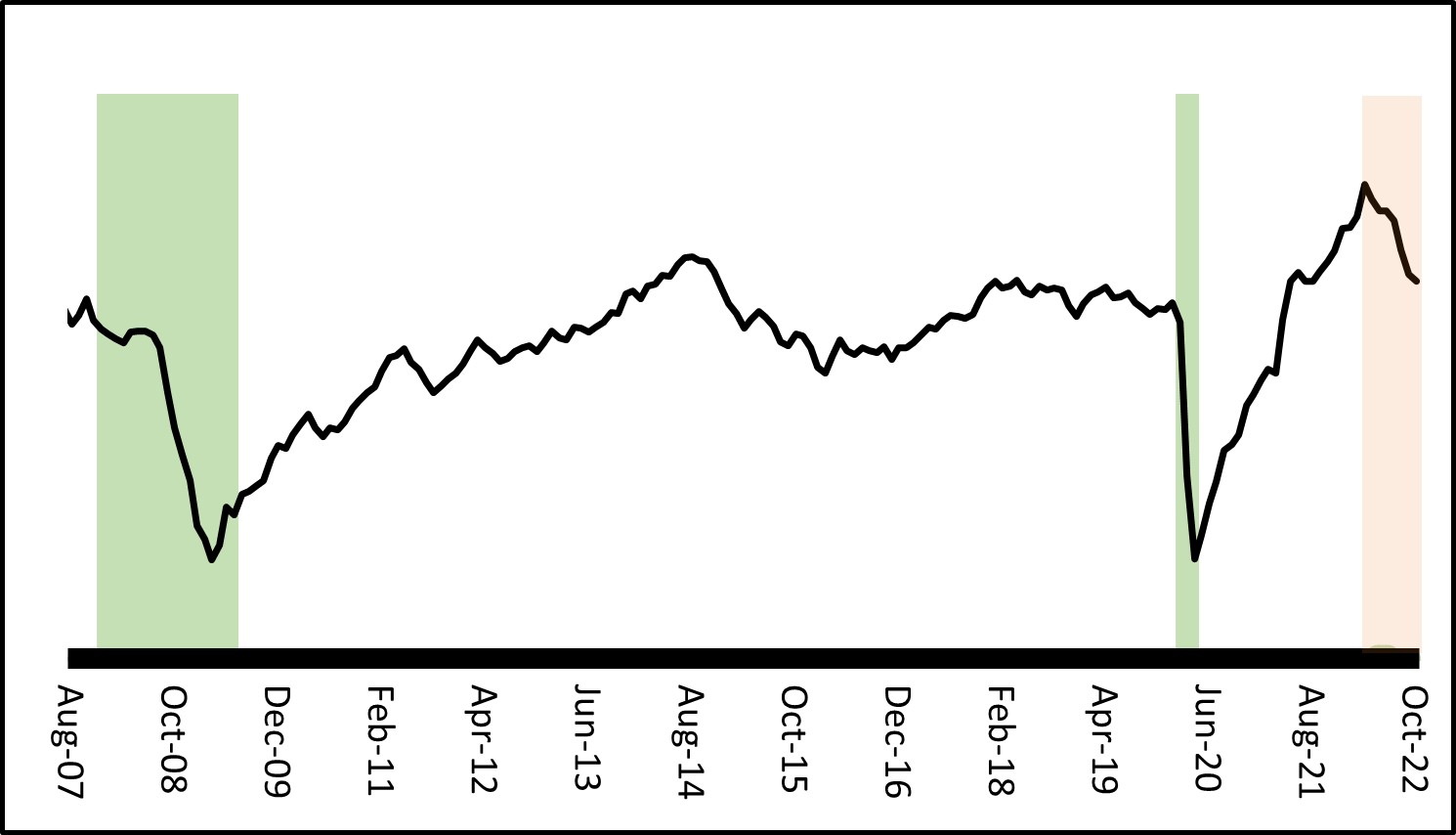

To forecast the region’s economic outlook, economists typically look at leading economic indicators. These indicators are variables that tend to decrease before overall economic activity slows down and rebound before a recovery. For Texas, the Dallas Fed combines into a single index eight indicators including the Texas value of the dollar, U.S. leading index, real oil price, well permits, initial claims for unemployment insurance, Texas stock index, help-wanted index and average weekly hours worked in manufacturing. Despite the strong labor market, the Texas Leading Index shows some signs of a slowdown since the monetary tightening by the Fed as can be seen in Figure 3. It is worth noting that the leading indicators did not pick up earlier recessions with significant lead time as can be seen in Figure 3.

Figure 3: The Dallas Fed Texas Leading Economic Indicators

Green areas indicate recessions, orange area indicates period of monetary tightening.

Source: The Dallas Fed

Summary

The Fed has shown a commitment to keeping rates high and prioritizing price stability. The effects of monetary tightening have been felt as the 12-month inflation rate was 7.1% in November, down from 9.1% in June. On December 14th, 2022, the Fed announced a 0.50 percentage point hike for the FF rate to be between 4.25% to 4.50% (compared to 1.5% to 1.75% in June). This is lower than some hikes earlier this year of .75 percentage point each.

Economists generally agree that the Fed should hold the course until price stability is achieved. In fact, studies covering historical disinflation episodes in several countries show that the output loss from reducing inflation was smaller, the faster the disinflation took place [2, 4]. This is referred to as the ‘cold turkey’ approach to disinflation.

____

Maroula Khraiche is an Associate Professor of Economics at The University of Texas Rio Grande Valley.

Andre Mollick is a Professor of Economics at The University of Texas Rio Grande Valley.

Endnotes

- Families First Coronavirus Response Act Will Cost $192 Billion. Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget. Apr 6, 2020.

- L. Ball. What determines the sacrifice ratio? In Monetary Policy, pages 155−−193. The University of Chicago Press, 1994.

- J. Jamerson, A. Duehren, and N. Andrews. Senate Approves Roughly $2 Trillion in Coronavirus Relief. Wall Street Journal. March 26, 2020.

- H. Katayama, N. Ponomareva, and M. Sharma. What determines the sacrifice ratio? a bayesian model averaging approach. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 81(5).

- N. McCarthy. What’s In The $1.9 Trillion Stimulus Package? Statista, March, 11 2021.

- E. Milstein and D. Wessel. What did the fed do in response to the covid-19 crisis. Brookings Institution, 2021.

Spring 2022 v18, n1

The end of globalization: Texas-Mexico border ports trends

Salvador Contreras

Over the past couple of years there have been hundreds if not thousands of reports suggesting that the end of globalization is upon us (for example [1]). They suggest that the benefits to trade have run their course and that one should expect a retrenchment, or at least a pause, to further expansion. Certainly, current geo-political events make the case to rethink existing alliances.

The Texas Border Region, by its very nature is highly connected to international commerce. The recent, if temporary, decision by the Texas Governor to institute enhance inspections of Mexican trucks along the Texas – Mexico border reminds us that international trade is much bigger then the ports that oversee its flows or the trucks that sit hours on end patiently awaiting their turn to reach a customs officer [2]. It also affects available inventory at our local stores and the prices we pay at the counter.

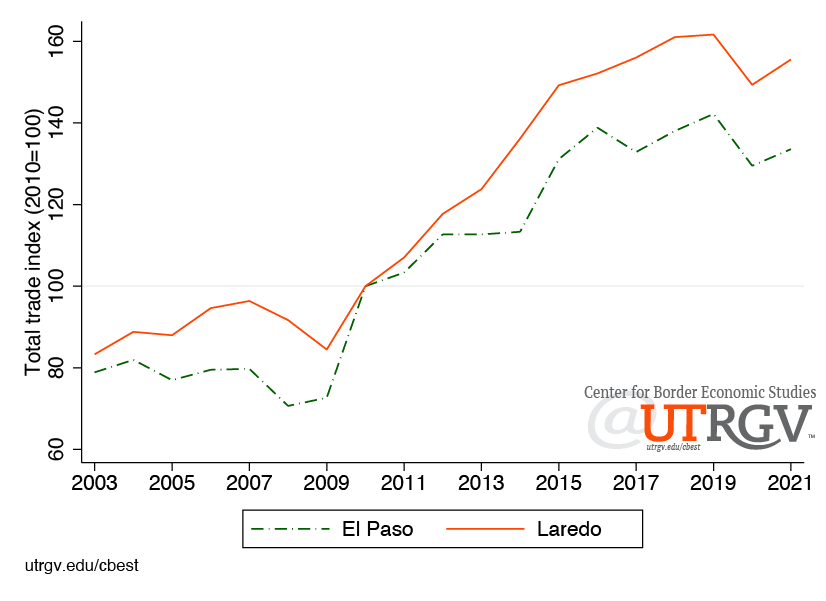

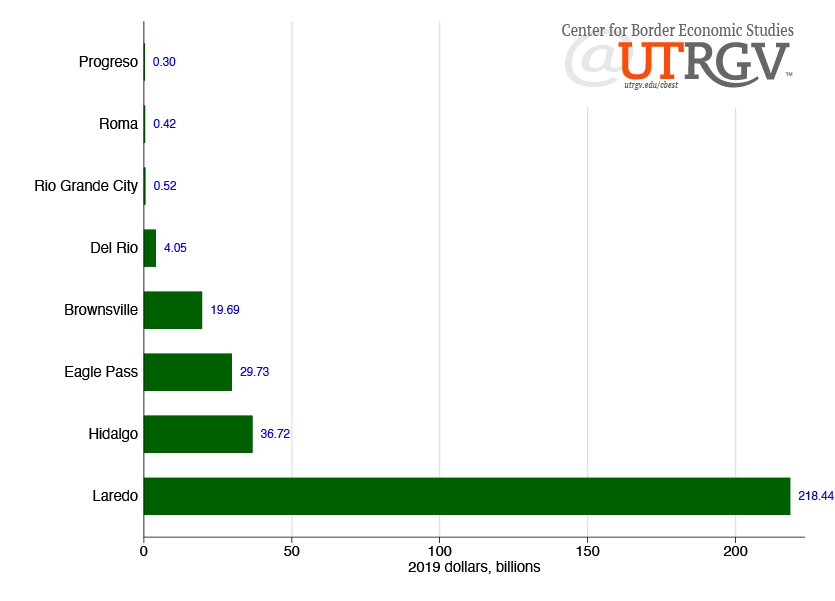

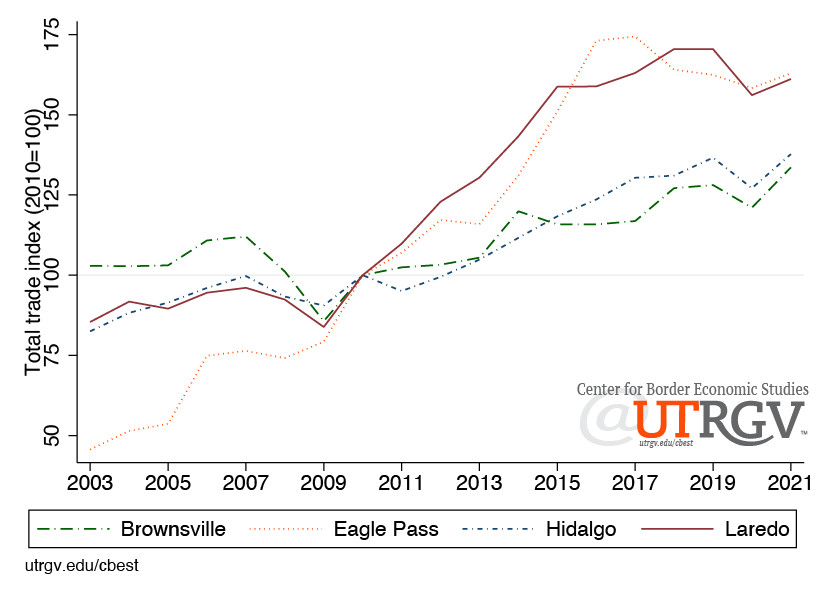

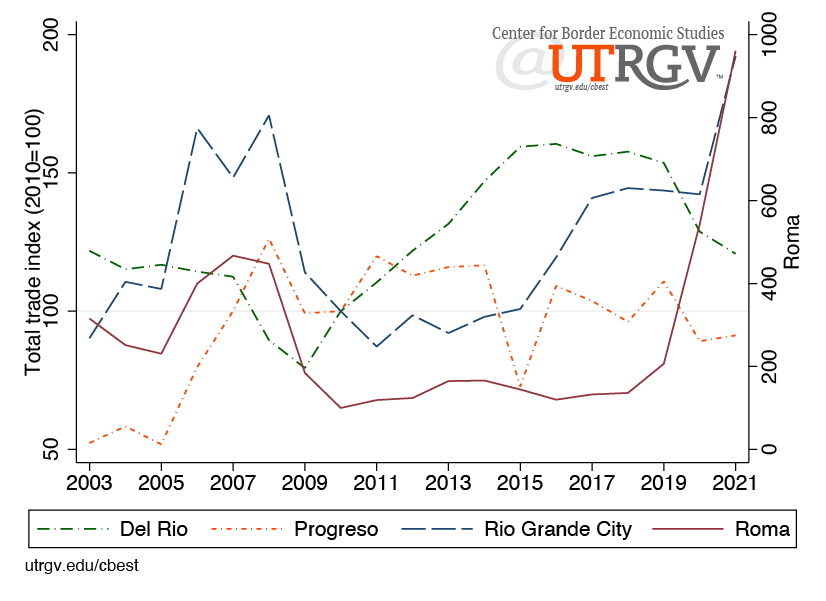

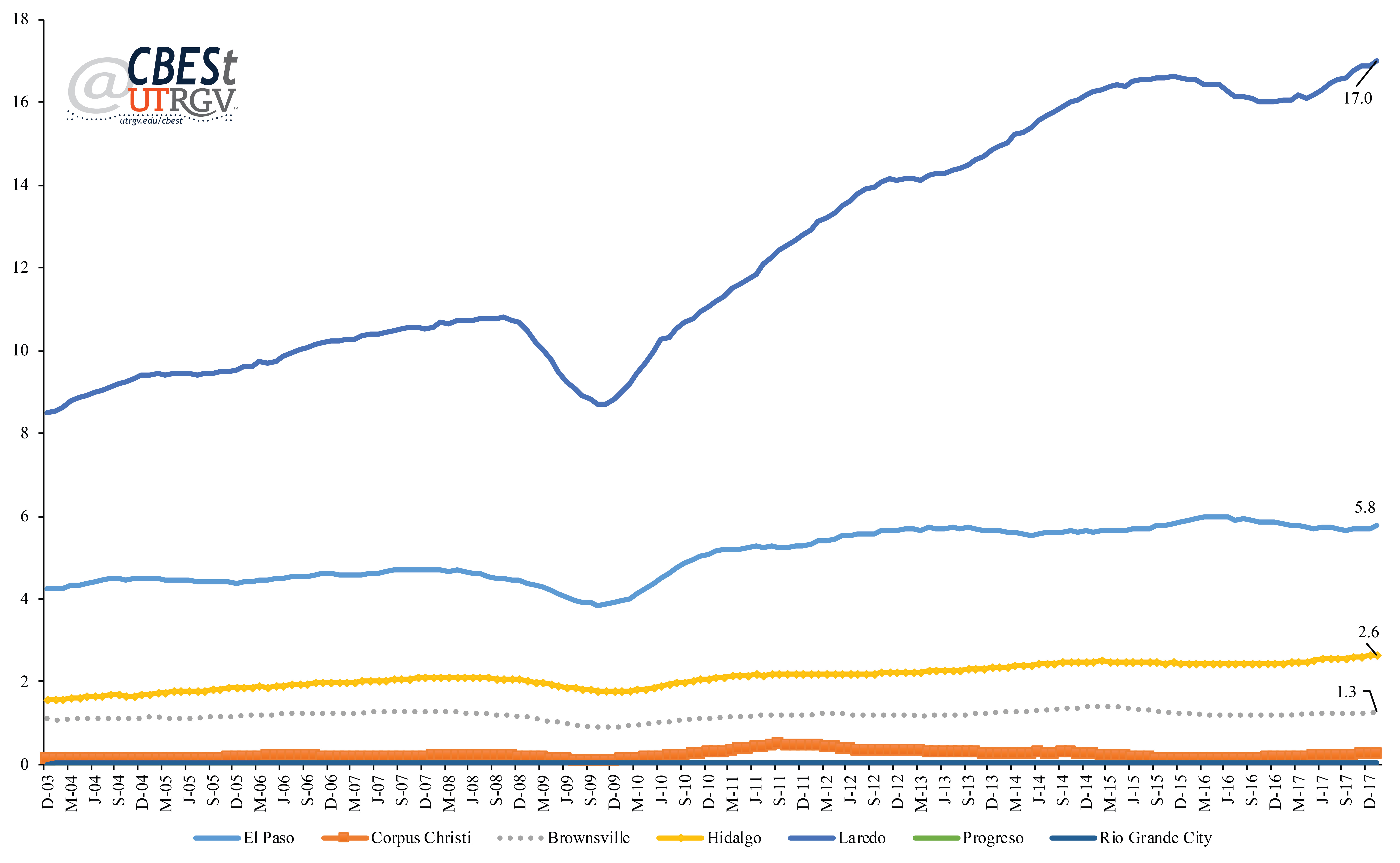

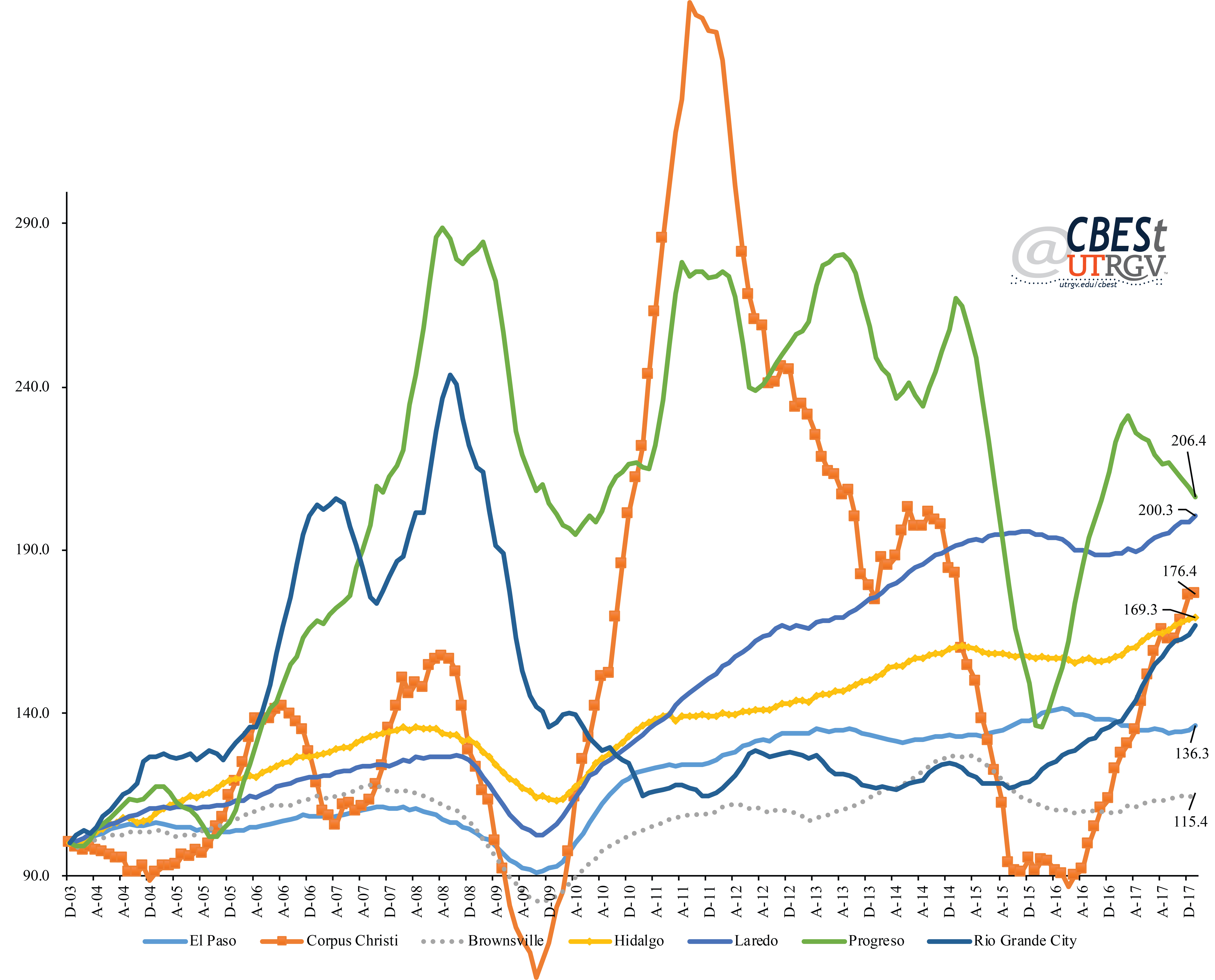

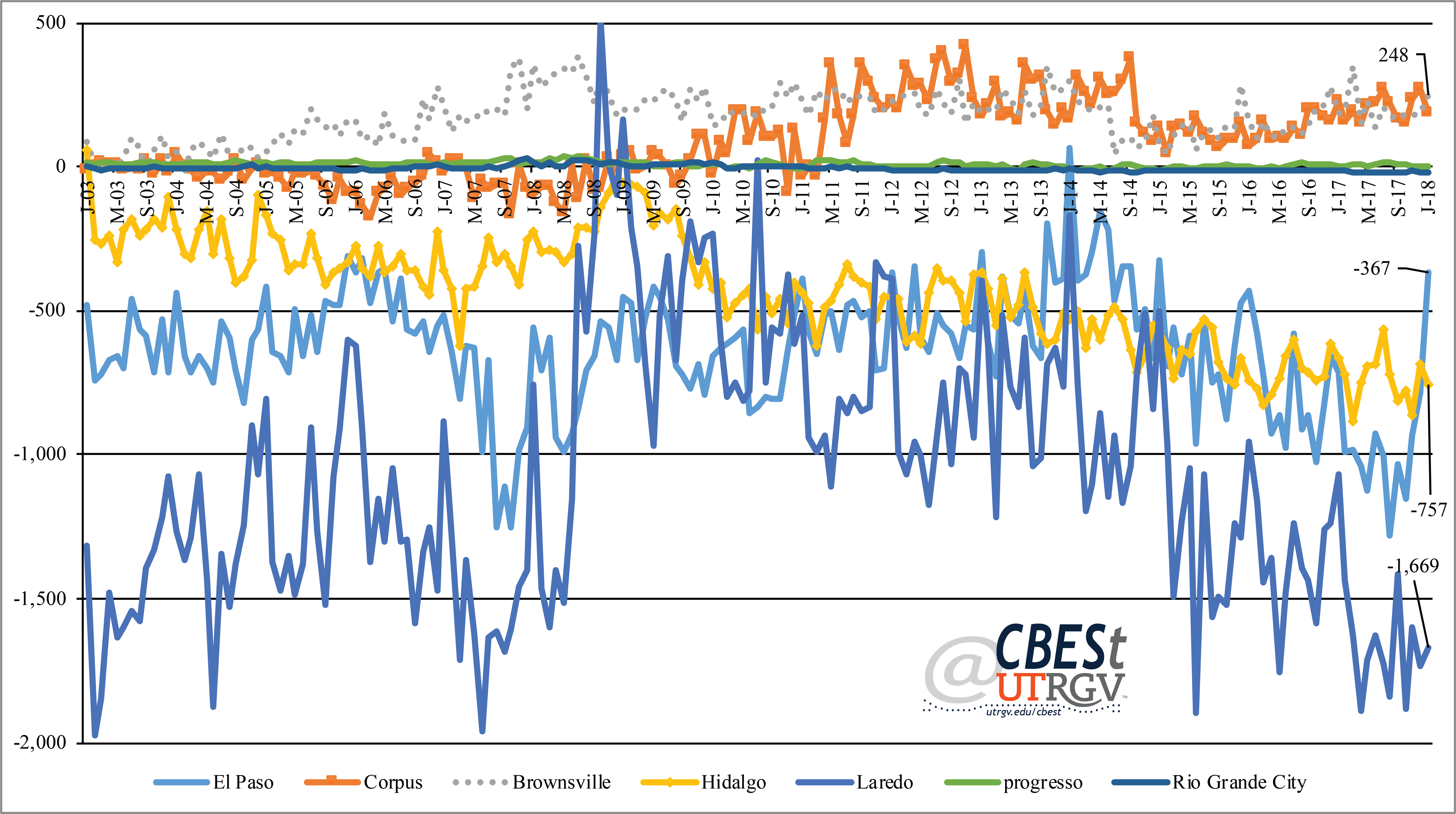

In this piece we study trends in international trade between the US and its top 3 trading partners. We show a clear deceleration in said activity. We then turn our attention to the Texas-Mexico border. We show that national trade patterns are reflected in trade flows through the El Paso District and Laredo District. Finally, we take a close look at trends at each of the ports in the Laredo District. We close by analyzing the composition of goods that flow through these ports.

Top trading partners

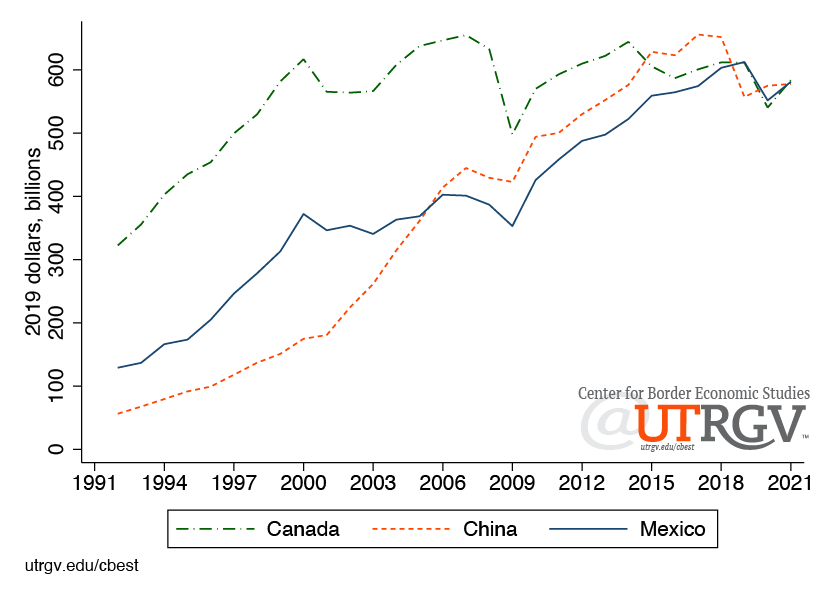

We begin by showing trade patters between the US and its top 3 trading partners. All values are inflation adjusted using the Producer Price Index and reflect 2019 dollars. We focus on the dollar value of total trade. Total trade is defined as exports plus imports.

Figure 1 shows US total trade [exports + imports] with Canada, China, and Mexico. Values are in billions of dollars. Notice that from the early 1990s up to 2000 trade flows are steadily growing. In 2000 trade between Mexico and Canada begin to move sideways while trade with China continues to increase. This period coincides with China joining the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001. Canada total trade with the US continued to go sideways through 2021. After the 2008 Financial Crisis we see that Mexico’s trade flows keep pace with China till 2017. Days into the Trump administration’s presidency, the US pulled out of the Trans-Pacific Partnership in early 2017. This and ensuing policies to decouple the US from what were seen by some as bad trade deals can be seen in the data as a decline in trade flows with China [3]. Trade with Mexico continued to grow until the 2020 COVID lockdowns. This allowed Mexico to become the US largest trading partner in 2019. In 2021 total trade with these three countries stood around $580 billion or $1.7 trillion combined or roughly 10% of US Gross Domestic Product (GDP).

Figure 1: Total trade, top 3 US trading partners

Source: US Census USA Trade

In general, trade has been trending down for the past 4 years. Is this a sign that the end of globalization is real? While, not likely. These trends suggest that it may no longer be expanding. Some argue that COVID and associated disruptions to manufacturing and supply chains is a likely culprit. Recent lookdowns of Shanghai affecting 26 million people, is a reminder that COVID is still around and that it continues to inflict damages to the world supply chain. No doubt, this is reflected in figure 1. Another reason can be placed on protectionist policies. For example, Trump era tariffs that covered a wide array of goods from steel to washing machines have also played role. In 2019, the US earned $79 billion in tariff revenue, double that of 2017 [4].