Phylogenetic Comparative Studies

Our work with behavioral development within species usually addresses processes that occur over days, weeks, months or years. This approach sometimes leads to questions about how behavioral variation may have changed over much longer time scales. This requires comparing species traits across many lineages. Work with parrotlets in Venezuela raised a number of questions that need different approaches to garner support. Such is the case with their contact calls.

A female nestling parrotlet uses wings to ascend nest cavity, following her father headed toward the door.

Contact calls in birds are often given in flight, because flight makes being in contact ever more important for connecting with social companions in dynamic situations. While reviewing video of contact calls in nestling parrotlets, we noticed a curious but apparently normal behavior – nestlings used wings strokes as they climbed up the nest cavity (Berg et al. 2013 J. Exp. Biol.). We were intrigued because of work of colleagues on evolutionary-developmental precursors of flight. Were we witnessing an ancestral form of flight?

Even more intriguing to us that during these wing-assisted ascents, nestlings gave contact calls as they breached the physical gap between parents and themselves. This made us curious about how vocal production and flapping flight might be related.

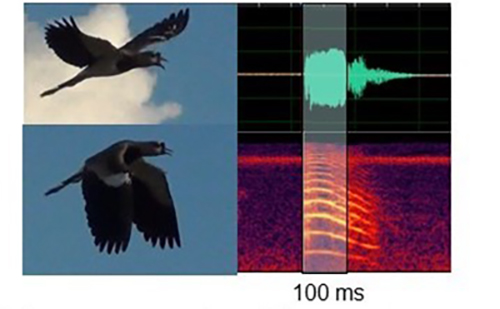

A Southern Lapwing filmed at Masaguaral, Venezuela synchronizes its power stroke (left) with most of the energy in its call (right).

To find out we used high-speed video and a microphone array to understand how the power stroke might be related to vocal production, or even aid in amplifying the signal, in a variety of species at our field site in Venezuela. Such a link had long been known to occur in the only other vertebrate group with forward flapping flight: the echolocating bats.

Many species, as predicted, synchronized their call with the power stroke. However, we noticed that parrotlets did not conform to a simple one-to-one relationship like the lapwing pictured above.

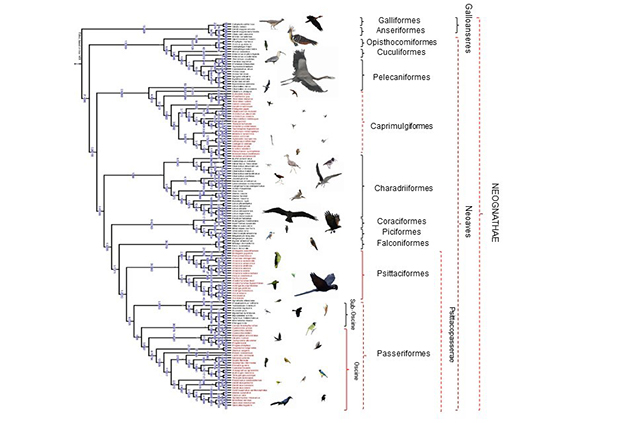

Phylogenetic tree of 150 bird species used to test for correlated evolution between power stroke, flight call duration and body mass, and to compare to vocal learners (red) and vocal non-learners (black) (Berg et al. 2019, Proc. R. Soc. B.)

We expanded the study to include data from 150 species vocalizing during flapping flight. In collaboration with bioinformaticians at the Texas Advanced Computing Center we conducted over 1 billion phylogenetically controlled regressions showing that parrots, songbirds and hummingbirds, the three bird groups that use vocal imitation, appear to have broken the cycle – their calls often far exceeded the powerstroke (Berg et al. 2019, Proc. R. Soc. B.), supporting the idea that an uncoupling of multiple motor systems controlling, wing, respiratory and vocal tract movements gave way to greater behavioral and vocal plasticity.